Temples in India (Cultural Geography) – A Detailed Analysis

- GS Paper 1: Indian Culture – Architecture & Art Forms, Cultural Geography, Heritage Sites

- GS Paper 2: Role of culture in diplomacy & international relations

- GS Paper 3: Conservation of Heritage Sites, Tourism Geography

- Prelims: Temple Architecture, Important Sites, UNESCO Sites, Religious Geography

- Geography Optional: Cultural Geography, Historical Geography, Settlement Patterns

India’s temples are not just religious structures; they are cultural landscapes that reflect regional geography, local materials, dynastic power, and evolving belief systems across two millennia. From the Gupta period through early-medieval kingdoms, the Cholas and Vijayanagara in the south, to modern conservation regimes, temple forms and locations map the historical and spatial imagination of Indian society.

Introduction

In cultural geography, temple architecture is understood as a spatial expression of faith, social organization, economic surplus, and regional identity. The distribution of temples across river valleys, coasts, plateaus, and mountains reveals how physical geography, pilgrimage networks, and trade routes shaped sacred centres and temple towns. Broadly, Indian temple architecture evolves from early Gupta prototypes (4th–6th century) to fully developed Nagara and Dravida forms in the early medieval era, grand Chola and Vijayanagara complexes (10th–16th century), and modern restorations and new constructions under colonial and post‑colonial regimes.

Factors Influencing Temple Geography

Climate conditions influence temple form: high curvilinear shikharas in the drier Indo‑Gangetic belt, sloping timber roofs in high‑rainfall Kerala, and compact stone vimanas in Tamil Nadu designed to withstand monsoon and cyclones. Mandapa layouts and open courtyards also respond to local climate, allowing shade and air flow in hot regions and compact shrines in colder Himalayan zones.

Building material choices follow geology: granite in the Deccan and Tamil region (e.g., Brihadeeswara, Hampi), sandstone in central and northern India (Khajuraho, Konark), laterite and brick in Bengal and Odisha, and marble in Rajasthan’s Jain temples. Dynastic patronage by Guptas, Pallavas, Chalukyas, Cholas, Rajputs, Marathas and others nurtured distinct regional idioms, while the relative absence of large Hindu temples under the Mughals altered the temple-building trajectory in Indo‑Islamic urban centres.

Cultural zones—Aryan‑Ganga plains, Dravidian south, Deccan, Himalayan belt, and tribal forest regions—each embed temples within vernacular traditions and pilgrimage circuits. Trade routes, such as the western coastal routes and the ancient Silk Route, encouraged temple foundations at ports (Dwarka, Rameswaram) and monastic cave complexes along caravan corridors (Ajanta‑Ellora).

Classification of Temple Architecture

Nagara School (North Indian)

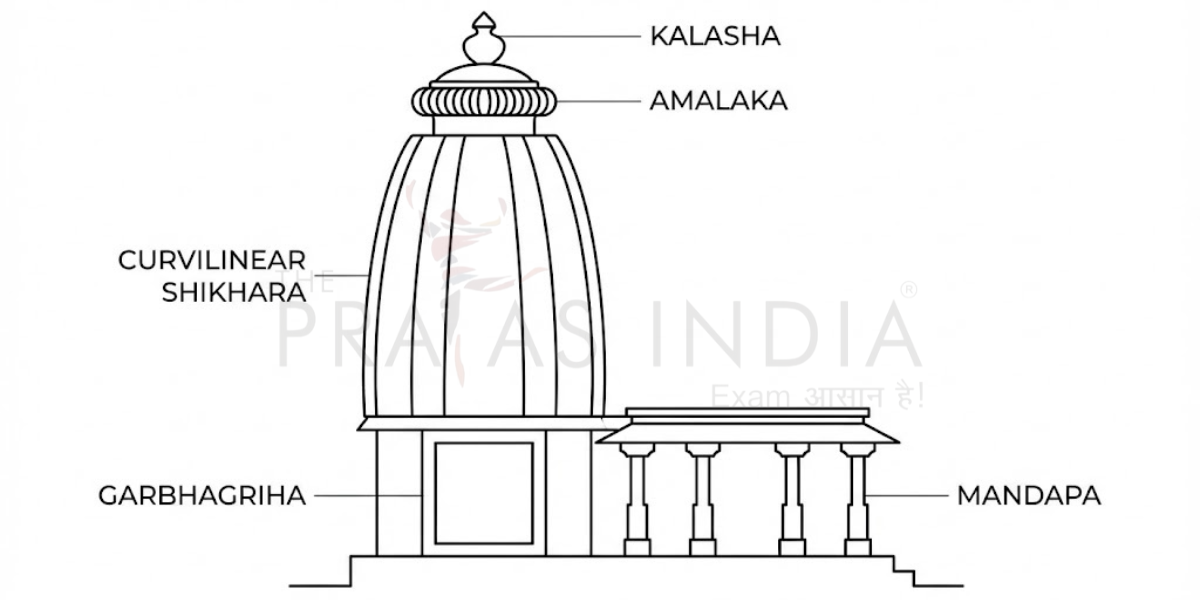

Nagara temples dominate north of the Vindhyas and are characterized by a square sanctum (garbhagriha) crowned by a curvilinear tower (shikhara), a pillared hall (mandapa), and crowning elements like the amalaka disk and kalasha finial. The plan often sits on a raised jagati (platform), with circumambulatory paths and rich exterior sculpture.

Important sub‑schools include:

- Odisha / Kalinga style: Distinct rekha deul (tall sanctum tower) with a square plan, fronted by a rectangular jagamohana (assembly hall), as seen at Lingaraja and the Sun Temple, Konark.

- Khajuraho style (Madhya Pradesh): Clustered shikharas rising like mountain ranges, extensive sculptural bands on jangha walls, exemplified by the Khajuraho Group of Monuments.

- Gujarat–Solanki style: Highly ornate carvings, intricate toranas and stepwells, seen at Modhera Sun Temple and Jain complexes like Dilwara (though largely marble).

Dravida School (South Indian)

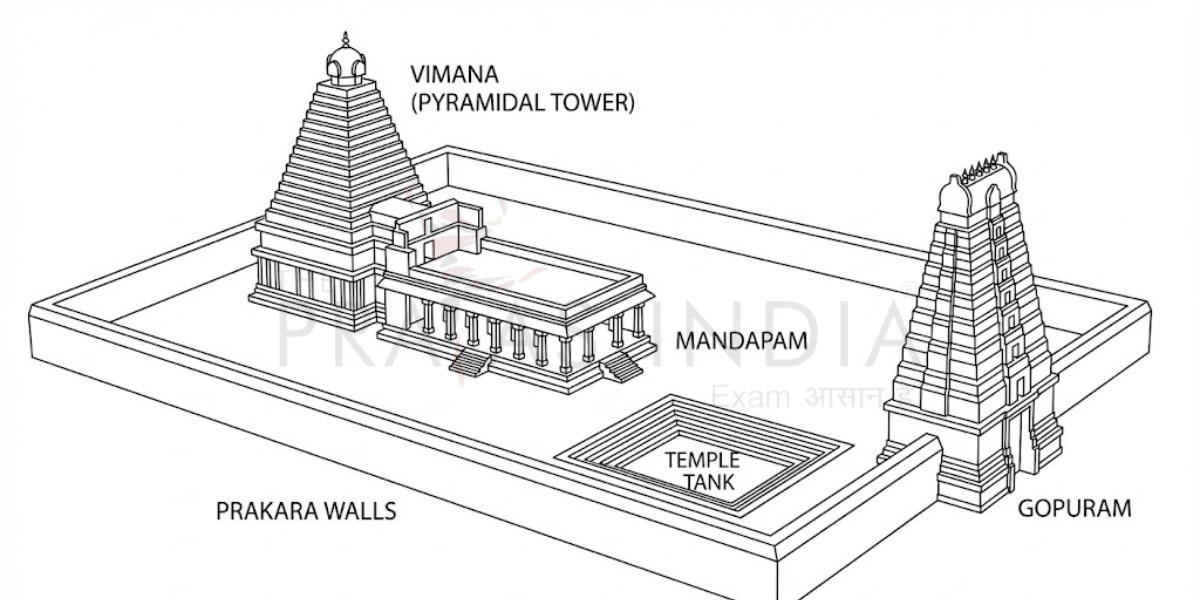

Dravida temples, prevalent in Tamil Nadu, parts of Karnataka and Andhra, feature a pyramidal vimana over the sanctum, enclosed prakaras (walls), colossal gopurams (entrance towers), and temple tanks for ritual bathing. Chola, Pallava, Pandya and Vijayanagara dynasties expanded these into multi‑courtyard complexes studded with mandapams and subsidiary shrines.

Key examples include the granite Brihadeeswara Temple at Thanjavur, Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram on the Coromandel coast, the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai, and Virupaksha Temple at Hampi. Their locations near fertile river deltas or trade‑rich plateaus show how agrarian surplus and commerce financed monumental construction.

Vesara School (Deccan Hybrid)

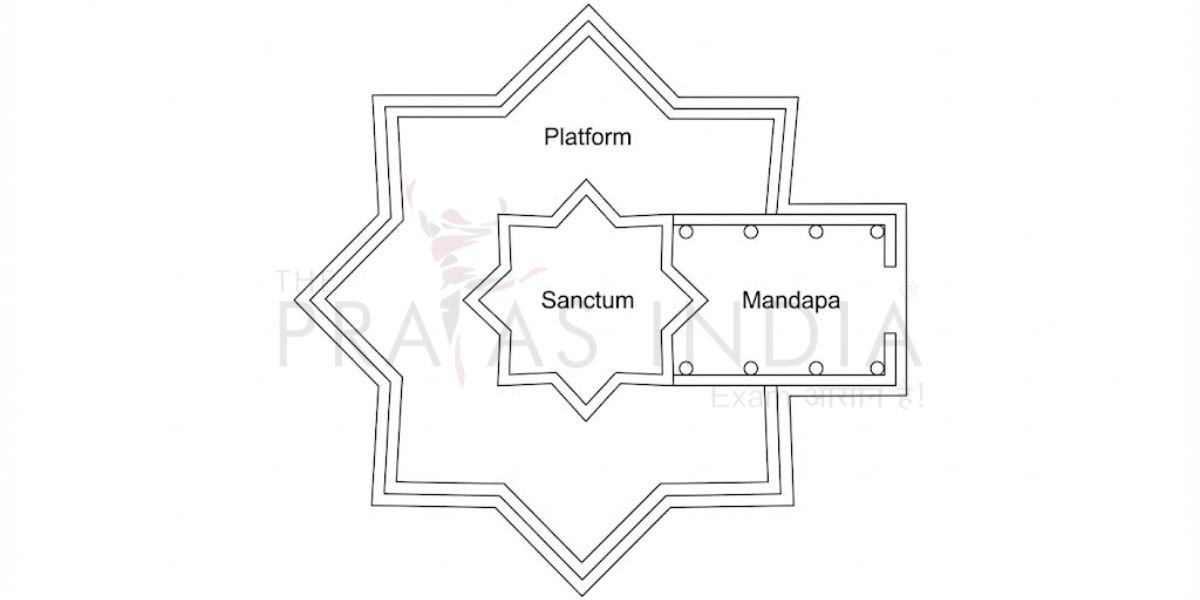

Vesara represents a hybrid of Nagara and Dravida that flourished under the Early Western Chalukyas of Badami and later the Hoysalas in Karnataka. These temples often have star‑shaped (stellate) platforms, lathe‑turned pillars, and soapstone sculpture allowing exquisite decorative detailing.

Examples include the Kailasa Temple at Ellora (monolithic yet displaying Dravido‑Nagara features), Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu, and Chennakesava Temple at Belur and Somnathpura. Their distribution across the Deccan plateau links them to regional capitals and trade corridors between coastal ports and interior markets.

Regional Distribution of Temples (Cultural Geography)

North India

Himalayan temples like Kedarnath and Badrinath sit along glacial river valleys, where compact stone shrines withstand cold climate, seismicity, and limited building space. Rajasthan’s marble Jain temples at Dilwara and Ranakpur use locally available marble and occupy hill slopes, while the Ganga plain hosts dense temple networks at Varanasi, Prayagraj, Ayodhya and Bodh Gaya, forming a “pilgrimage corridor” along major rivers.

Kashmir’s Martand Sun Temple (now in ruins) reflects early stone architecture adapted to a high‑altitude valley, showing Central Asian influences via historic trade links.

East India

Odisha’s Kalinga temples (Lingaraja, Konark) line the coastal plain and Mahanadi delta, where laterite and sandstone enabled tall rekha deuls visible from afar. Bengal’s brick and terracotta temples (Bishnupur) use riverine clay and display panels depicting local agrarian and river life.

Assam’s Kamakhya Temple crowns Nilachal Hill above the Brahmaputra, integrating Shaktism with a powerful river landscape prone to monsoon flooding.

South India

Tamil Nadu houses dense Dravidian complexes at Kanchipuram, Thanjavur, Chidambaram, Madurai and Rameswaram, often linked to fertile Cauvery and Vaigai basins. Karnataka combines Vesara (Hoysala) temples at Belur and Halebidu with rock‑cut shrines at Badami, Aihole and Pattadakal on the Deccan plateau.

Kerala’s temples, like Padmanabhaswamy at Thiruvananthapuram, feature timber structures and steep, tiled roofs suited to heavy monsoon rainfall. Andhra–Telangana’s Kakatiya sites such as Ramappa Temple use sandbox foundations to cope with black soil and seismic conditions.

West and Central India

Gujarat’s Solanki temples (Modhera Sun Temple) and stepwells integrate water management with worship on semi‑arid plains. Maharashtra’s Ajanta–Ellora and Elephanta cave temples in basalt cliffs show how the Western Ghats and coastal hills were sculpted into sacred spaces near trade routes.

In central India, Khajuraho’s temples rise amidst the Bundelkhand plateau, once controlling routes between the Ganga valley and Deccan, while Chhattisgarh’s tribal‑influenced shrines blend megalithic traditions with forested landscapes.

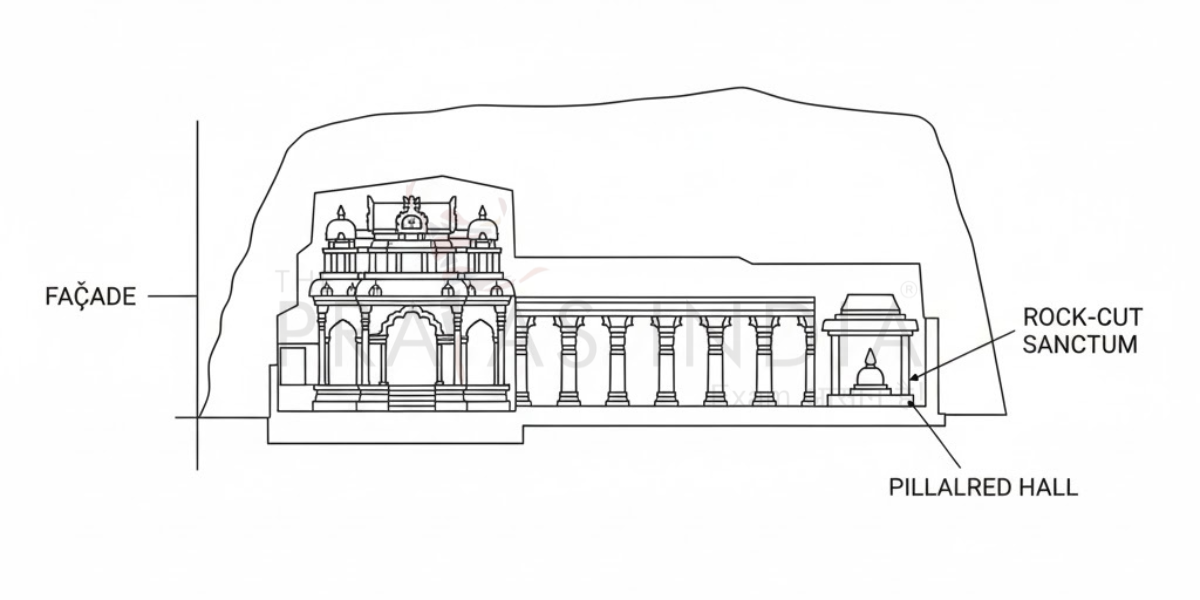

Cave Temples of India

Rock‑cut cave temples mark an early phase of Indian sacred architecture from about 2nd century BCE to 10th century CE. Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra contain Buddhist chaitya halls and viharas carved into a horseshoe‑shaped gorge, while Ellora’s multi‑faith complex includes Buddhist, Hindu and Jain caves, culminating in the monolithic Kailasa Temple.

Elephanta Caves near Mumbai harbour Shaivite panels like the Maheshmurti, reflecting maritime linkages of the Konkan coast, and Badami Caves in Karnataka show early Chalukya experimentation in Deccan sandstone cliffs. These rock‑cut forms prefigure later structural temples and highlight how geology (basalt, sandstone) permitted large‑scale excavation.

UNESCO World Heritage Temple Sites

Khajuraho Group of Monuments in Madhya Pradesh lies on the Bundelkhand plateau and is famous for clustered shikharas and detailed sculpture, illustrating Chandela patronage and the region’s semi‑arid landscape. Konark’s Sun Temple stands on Odisha’s coastal plain, where salt‑laden winds and cyclones have contributed to structural decay, making coastal conservation critical.

Brihadeeswara Temple in Thanjavur, on the fertile Cauvery delta, symbolises Chola power and hydraulic prosperity. The Group of Monuments at Hampi occupies a boulder‑strewn Tungabhadra valley, where granite outcrops become part of temple and bazaar layouts. Mahabalipuram on the Coromandel coast shows Pallava rock‑cut and structural temples vulnerable to sea‑spray, erosion and tsunamis.

Cultural Geography: Festivals & Pilgrimage Circuits

Pan‑Indian circuits such as Char Dham (Badrinath, Dwarka, Puri, Rameswaram), the twelve Jyotirlingas, Shakti Peethas, and the Jagannath Rath Yatra create spatial networks binding distant regions. These circuits foster temple towns, lodging facilities, markets and transport nodes along major rivers and coasts, shaping India’s settlement geography.

Regional circuits like Sabarimala in Kerala use forested hill routes and seasonal pilgrim flows that significantly affect local economies and ecology. Over time, these flows have transformed small shrines into major urban centres like Varanasi, Madurai and Puri.

Socio‑Economic & Cultural Significance

Temples often anchor urban geography: cities like Varanasi, Madurai, Puri, Kanchipuram and Ujjain grew around temple complexes, processional streets, ghats, and sacred tanks. Their spatial layout—concentric streets (Madurai), riverfront ghats (Varanasi), or hilltop shrines (Tirupati)—structures daily flows of people, goods and rituals.

Economically, temple tourism generates employment in hospitality, transport, food, flower trade, ritual services, and handicrafts such as stone carving and metal icon making. Historically, temples controlled land endowments and irrigation tanks, functioning as local fiscal and administrative centres as seen in Chola and Vijayanagara regions.

Culturally, temples sustain dance (Bharatanatyam, Odissi), music (Carnatic concerts in temple festivals), and ritual theatre (Kathakali, Yakshagana), embedding performing arts in sacred space. Contemporary conservation must therefore protect both tangible structures and intangible practices tied to them.

Threats to Temple Heritage

Rapid urbanisation leads to encroachments on temple tanks, processional routes and view corridors, especially in older temple towns. Road widening, illegal construction and unregulated commercialisation can sever visual and ritual links between shrine, water bodies and surrounding landscape.

Weathering and climate pose serious risks: monsoon‑driven erosion, salinity ingress in coastal temples like Konark and Mahabalipuram, and freeze–thaw stress in Himalayan shrines. Air pollution and acidification, similar to issues documented near marble monuments, also darken and chemically damage stone surfaces around busy urban temples.

Tourism pressure strains fragile sites through overcrowding, litter, vibration from traffic and inadequate visitor management. Illegal quarrying or mining near heritage landscapes, as raised in several conservation reports, can destabilise hill temples and cave systems. Natural disasters—floods, landslides, cyclones and earthquakes—add another layer of vulnerability, especially in Himalayan and coastal belts.

Case Studies

Hampi: Landscape–Architecture Harmony

Hampi, on the Tungabhadra River in Karnataka, demonstrates close integration of Vijayanagara temples with granitic boulder hills, irrigated fields and bazaar streets. The Virupaksha and Vittala complexes are aligned with river ghats and market axes, illustrating how sacred geography structured the imperial capital’s economy and settlement pattern.

Kedarnath: Flood Vulnerability

Kedarnath, perched near the Chorabari glacier in Uttarakhand, sits in a narrow valley prone to cloudbursts and glacial lake outburst floods. The 2013 floods highlighted exposure of Himalayan temple settlements to extreme weather, calling for zoning regulations, controlled pilgrim numbers and resilient infrastructure without disturbing the shrine’s cultural aura.

Khajuraho: Sculpture & Conservation

Khajuraho’s temples in Bundelkhand plateau are renowned for narrative and erotic sculptures, which have generated debates about morality, art and heritage interpretation. Conservation challenges include balancing global tourism, structural stability of sandstone towers, and respectful on‑site explanation of iconography for students and visitors.

Konark: Coastal Climate Stress

The Sun Temple at Konark, originally positioned close to the Bay of Bengal, has suffered from salt‑laden winds, cyclones and a high water table that weakened its masonry. Colonial‑era filling of its jagamohana, while stabilising the structure, altered original spatial experience; ongoing efforts must address shoreline change and corrosion.

Chidambaram Nataraja: Philosophical Symbolism

Chidambaram Temple in Tamil Nadu embodies Shaiva philosophy through its layout: the Chit Sabha’s empty space symbolises the formless Brahman, while the Nataraja image represents cosmic dance. Its location near the fertile Cauvery delta ties metaphysical ideas to a prosperous agrarian landscape and long‑standing ritual and scholarly traditions.

UPSC‑Relevant Question Angles

For GS‑1, questions have focused on distinguishing Nagara and Dravida styles, explaining features of cave architecture, and describing how geography influenced temple forms. Prelims map‑based items frequently point to locations of Khajuraho, Konark, Hampi, Mahabalipuram, Ajanta, Ellora and major pilgrimage circuits such as Char Dham and Jyotirlingas.

Optional geography questions may treat temples as cultural landscapes—asking candidates to analyse spatial patterns of temple towns, role of pilgrimage in regional development, or human–environment interaction in sacred sites like Kedarnath or Sabarimala. Preparing short comparison tables (Nagara–Dravida–Vesara, rock‑cut vs structural) and labelled diagrams is especially useful for mains answers.

FAQs – Temples in India

Q1. What are the main architectural styles of Indian temples?

The primary styles are Nagara (North Indian), Dravida (South Indian), and Vesara (Deccan). Each has distinct features in shikhara design, layout, and ornamentation.

Q2. Which is the oldest known temple in India?

The Mundeshwari Temple (Bihar), dating to around the 4th century CE, is considered one of the oldest surviving functional temples.

Q3. What are the key features of Nagara-style temples?

Nagara temples have a curvilinear shikhara, no boundary walls, and usually a tall, tower-like structure. Famous examples include Khajuraho and Konark Sun Temple.

Q4. What defines Dravida-style temples?

Dravida temples have pyramidal vimanas, massive gopurams, and enclosure walls. Examples include Brihadeeswara Temple and Meenakshi Amman Temple.

Q5. What is the Vesara style?

The Vesara style blends features of Nagara and Dravida. It is prominent in Karnataka. Examples include Hoysaleswara Temple and Pattadakal Group of Monuments.

Q6. Which temples are important for cultural geography study?

Konark, Khajuraho, Brihadeeswara, Kedarnath, Meenakshi, Jagannath, Dilwara Jain Temples, Hampi temples, and Sanchi (stupa architecture comparison).

Q7. Why do temples vary so much across India?

Variations arise due to regional climate, local materials, ruling dynasties, artistic traditions, and religious influences.

Q8. Which temples are significant for UPSC exam preparation?

Khajuraho, Konark, Lingaraja, Sun Temple Modhera, Dilwara Temples, Kailasa at Ellora, Shore Temple, Brihadeeswara, Virupaksha at Pattadakal, and Sanchi Stupa (comparative study).

Conclusion

Temples in India function as “geographical texts” that encode ecological settings, available materials, political power, trade networks, and religious worldviews into stone, brick and wood. From Nagara spires of the northern plains to Dravidian gopurams of the south and Vesara hybrids of the Deccan, their regional diversity mirrors India’s physical and cultural heterogeneity. Safeguarding these living sacred landscapes requires integrating conservation science, sustainable tourism, local community participation and sensitivity to both ritual continuity and architectural integrity.