Section 498-A IPC (BNS Sec 85): Supreme Court’s 2-Month Cooling-Off Period and Its Implications

In July 2025, the Supreme Court of India upheld the Allahabad High Court’s directive introducing a mandatory two-month “cooling-off” period before any arrest under Section 498-A IPC (BNS Sec 85), except in cases involving serious physical injury or offenses with punishment exceeding ten years.

This ruling, aimed at balancing the prevention of misuse and protection of victims, has ignited intense debate in legal, social, and women’s rights circles.

Understanding Section 498-A IPC (BNS Sec 85)

Section 498-A (BNS Sec 85), enacted in 1983, criminalises cruelty against married women by their husband or his relatives.

The provision covers:

- Physical violence or mental harassment likely to drive a woman to suicide or cause grave harm.

- Dowry-related harassment or unlawful demands for property.

Punishment:

- Imprisonment of up to three years

- Fine (amount determined by court discretion)

Its primary aim is to deter domestic violence and provide legal recourse for victims in a largely patriarchal social setting.

The Supreme Court’s July 2025 Ruling

Background

- In 2022, the Allahabad High Court issued guidelines requiring police to delay arrests for two months after an FIR under Section 498-A (BNS Sec 85).

- The idea was to allow for Family Welfare Committee (FWC) mediation before legal action.

SC’s Endorsement

The Supreme Court upheld these guidelines without seeking detailed feedback from the State government.

Key points of the judgment:

- No arrests or coercive action during the first 60 days post-FIR (exceptions apply).

- All complaints to be referred to FWCs for possible amicable resolution.

- Intended goal: filter out frivolous or malicious cases while preserving genuine grievances.

Why This Ruling is Controversial

Impact on Complainants

- Delays in protection: Victims may remain at risk during the two-month wait.

- Fear of retaliation: Perpetrators may threaten or harm complainants during this period.

- Reduced trust in police: Mandatory waiting periods could signal institutional apathy.

Impact on Law Enforcement

- Slower investigations: Early evidence may be lost, making convictions harder.

- Operational confusion: Police officers must balance the court directive with procedural urgency in severe cases.

The Misuse Debate

Concerns about misuse of Section 498-A (BNS Sec 85) have been raised for years:

- Past court observations have noted instances where the provision was allegedly used to settle personal scores.

- However, no comprehensive national data confirm widespread misuse.

Key statistics:

- Conviction rate ~18% (higher than many other IPC sections).

- Over 1.34 lakh cases registered under Section 498-A (BNS Sec 85) in 2022.

- Surveys indicate under-reporting due to stigma, fear of retaliation, and family pressure.

Low conviction rates often reflect:

- Poor investigation quality.

- Victims withdrawing complaints under social or economic pressure.

- Not necessarily a high rate of false allegations.

Domestic Violence, Family Law, and ADR

- Alternative dispute resolution (ADR), like mediation, works well for divorce and child custody disputes.

- But domestic violence cases involve criminal conduct, where safety and deterrence outweigh reconciliation.

- Experts argue that mandatory conciliation before protection undermines the urgency of penal enforcement.

Legal and Social Implications

- Erosion of Uniform Criminal Law – Selectively suspending enforcement in one IPC section creates inconsistency.

- Potential for Increased Violence – Perpetrators may act with impunity during the delay.

- Judicial Overreach Concerns – Court-imposed procedural suspension without legislative amendment could set a precedent for bypassing parliamentary lawmaking.

- Risk to India’s Gender Justice Commitments – India’s obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) require robust protection laws.

What Experts Suggest

- Case-by-case discretion for immediate arrest in high-risk cases, rather than a blanket cooling period.

- Strengthening investigation capacity in domestic violence units.

- Providing safe shelters and witness protection for complainants during the waiting period.

- Publishing transparent misuse data to guide policy.

Relevance for Competitive Exams

-

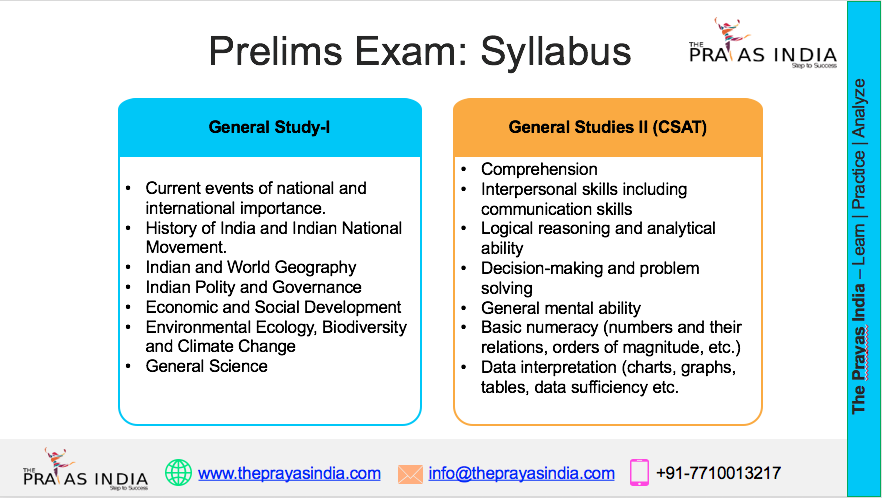

Prelims

- IPC provisions, year of amendment.

- CrPC arrest powers and safeguards.

-

Mains / Descriptive

- Debate on misuse vs protection.

- Gender justice vs individual rights.

-

Interview

- Opinion on legal reforms and women’s protection laws.

-

Judiciary Exams

- Direct questions on offence classification, punishment, and court interpretations.

The Supreme Court’s two-month cooling-off directive under Section 498-A IPC (BNS Sec 85) reflects an attempt to address misuse concerns but risks weakening victim protection in genuine domestic violence cases.

Balancing fairness to the accused with safety for complainants requires flexible, evidence-driven safeguards, not rigid delays.

A truly just approach would involve faster investigations, protective measures, and better judicial oversight—ensuring that the system fails neither the innocent nor the vulnerable.

![Prayas-तेजस [UPSC CSE Sociology Optional] – Online & Offline](https://theprayasindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Prayas-तेजस-UPSC-CSE-Optional-Subject-The-Prayas-India-300x300.png)

![Prayas-सूत्र [UPSC CSE Materials (Hardcopy)]](https://theprayasindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Prayas-सूत्र-UPSC-CSE-Study-Materials-Hardcopy-The-Prayas-India-300x300.png)

![Prayas-मंत्रा [UPSC CSE CSAT]](https://theprayasindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Prayas-मंत्रा-UPSC-CSE-CSAT-The-Prayas-India-300x300.png)

![Prayas सारथी [UPSC CSE One on One Mentorship]](https://theprayasindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Prayas-सारथी-UPSC-CSE-One-on-One-Mentorship-The-Prayas-India-300x300.png)