Western Ghats – Landscape, Biodiversity, and Conservation Imperatives

- GS Paper 1: Physical Geography, Indian Physiography, Biogeography

- GS Paper 3: Environment, Climate Change, Conservation, Ecology

- Prelims: Biodiversity Hotspots, Protected Areas, Rivers, Monsoon Mechanisms

- Geography Optional: Geomorphology, Climatology, Biogeography, Environmental Geography

Introduction

The Western Ghats, also known as the Sahyadri Mountains, are a 1600-km-long mountain chain running parallel to the western coast of India. Stretching from the Tapti Valley in Gujarat to Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu, this ancient mountain system is one of the most ecologically significant landscapes in the world.

UNESCO designates the Western Ghats as one of the “world’s eight hottest biodiversity hotspots” because of:

- extremely high species richness,

- exceptional endemism,

- ancient evolutionary history, and

- severe levels of habitat loss.

Ecologically, they function as the climate regulator of Peninsular India, determining the distribution of rainfall, monsoon intensity, hydrology, and biodiversity patterns. Nearly 245 million Indians depend on rivers that originate from these mountains, making the Ghats a national ecological lifeline.

Geological Formation & Physical Geography

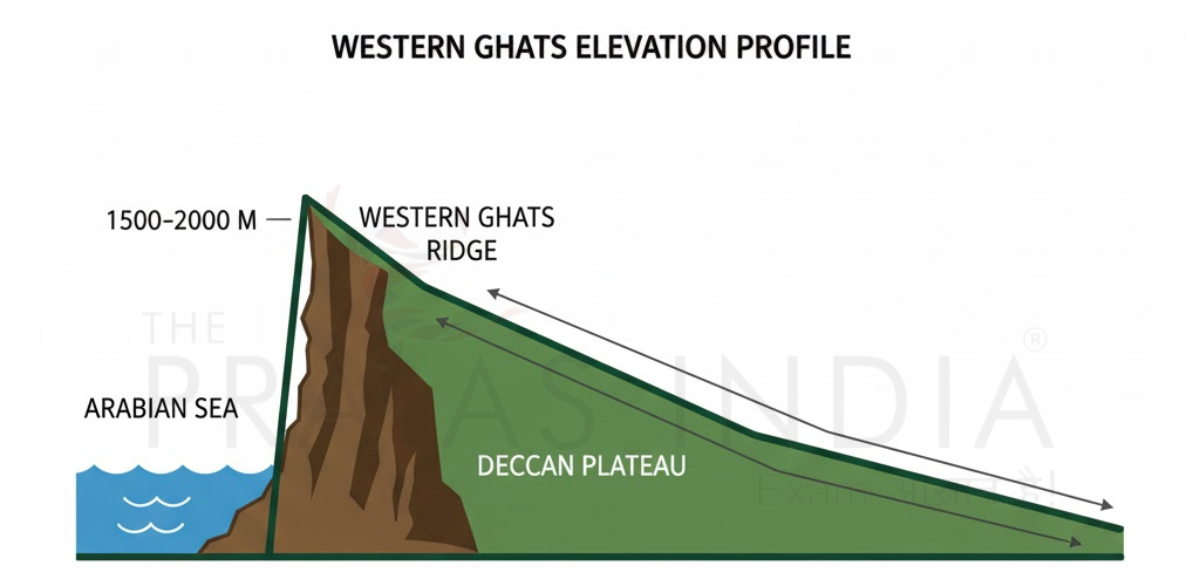

Geologically, the Western Ghats formed due to uplift along the western edge of the Deccan Plateau during the early Cenozoic era (around 60–65 million years ago). The uplift is associated with:

- faulting and rifting along the western continental margin,

- separation of India from Madagascar,

- extensive volcanic activity (Deccan Traps), and

- later tectonic adjustments.

Thus, the Western Ghats represent the western escarpment of the Deccan Plateau, rising sharply from the coastal plains and gently descending eastward.

Altitude & Peaks

Most of the range lies between 900–1600 m.

Key peaks include:

- Anaimudi (2695 m) – highest peak in South India

- Doddabetta (2637 m)

- Mullayanagiri (1930 m)

- Kudremukh (1894 m)

- Mahabaleshwar (1438 m)

Geographical Stretch

- Northern limit: Valley of the Tapti River

- Southern limit: Kanyakumari

- Total length: ~1600 km

- States covered: Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu

Major Physiographic Sections

The Western Ghats can be divided into three broad physiographic segments:

A. Northern Western Ghats (Gujarat–Maharashtra–Goa)

- Characterized by basaltic plateaus of Deccan Traps.

- Ranges include Sahyadri range, Harishchandragad-Kalsubai range.

- Important peaks:

- Kalsubai (1646 m) – highest in Maharashtra

- Mahabaleshwar plateau

- Known for steep escarpments overlooking Konkan.

B. Central Western Ghats (Karnataka Region)

- One of the most continuous and elevated sections.

- Densely forested; heavy rainfall zones.

- Major peaks:

- Kudremukh

- Mullayanagiri

- Famous for coffee cultivation, dense evergreen forests, and shola ecosystems.

C. Southern Western Ghats (Kerala–Tamil Nadu)

- Highest elevations in the Ghats.

- Home to the Anamalai, Palani, and Cardamom Hills.

- Contains Anaimudi, Eravikulam Plateau, Silent Valley forests.

- Extremely high endemism of plants, amphibians, and mammals.

Rivers Originating from the Western Ghats

Because of their elevation and rainfall, the Western Ghats are often called the “Water Tower of Peninsular India.”

West-Flowing Rivers (Short, swift, high-energy)

- Sharavathi → forms Jog Falls

- Mandovi

- Zuari

- Netravati

East-Flowing Rivers (Longer rivers forming major basins)

- Tributaries of Godavari

- Krishna and tributaries (Bhima, Tungabhadra)

- Kaveri (origin: Talakaveri, Karnataka)

These rivers support hydropower, irrigation, drinking water supply, and biodiversity-rich riparian ecosystems.

Climate & Monsoon Influence

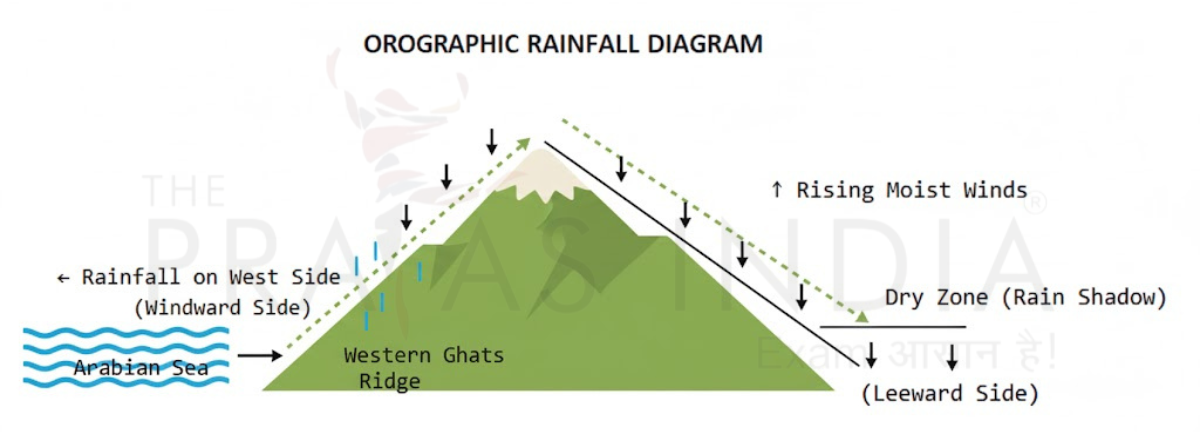

The Western Ghats act as a massive orographic barrier to the southwest monsoon.

Orographic Rainfall

- Moist monsoon winds from the Arabian Sea rise against the windward slopes.

- Cooling → condensation → heavy rainfall.

- Areas like Agumbe, Mahabaleshwar, Wayanad, Idukki receive 4000–7000 mm annually.

Rain Shadow Effect

The leeward side (Maharashtra plateau, north interior Karnataka, Tamil Nadu) receives 500–900 mm, causing:

- semi-arid conditions

- rain-fed agriculture

- distinct vegetation types

Climate Regulation

- Stabilizes monsoon rhythm

- Supports perennial rivers

- Regulates carbon and hydrological cycles

Biodiversity of the Western Ghats

The Western Ghats contain over 30% of India’s plant, reptile, and amphibian species—many found nowhere else on Earth.

Flora

- Tropical evergreen forests

- Semi-evergreen forests

- Moist deciduous forests

- Shola forests (high-elevation stunted forests with grasslands)

- Myristica swamps (ancient freshwater swamp forests)

Fauna

- Nilgiri tahr (endemic)

- Lion-tailed macaque (critically endangered)

- Malabar civet

- King cobra

- Nilgiri martens, flying squirrels, amphibian diversity (350+ species)

Unique ecosystems like shola–grassland mosaics support endemic orchids, amphibians, and birds (e.g., Nilgiri flycatcher).

Protected Areas in the Western Ghats

National Parks

- Silent Valley (Kerala)

- Eravikulam (Kerala)

- Bandipur (Karnataka)

- Periyar (Kerala)

Biosphere Reserves

- Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve

- Agasthyamalai Biosphere Reserve

UNESCO World Heritage Cluster

39 sites, including reserves in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala.

Human Settlements & Cultural Geography

Tribal Communities

- Todas, Kotas (Nilgiris)

- Kurumbas, Irulas

- Maintain traditional ecological knowledge, pastoralism, sacred groves.

Agriculture

- Tea (Nilgiris, Munnar)

- Coffee (Coorg, Chikkamagaluru)

- Cardamom, pepper, spices (Idukki, Wayanad)

Historic Passes

- Palghat Gap – major climatic and cultural corridor

- Thal Ghat, Bhor Ghat – historically important trade routes

Environmental Issues & Threats

The Western Ghats face enormous developmental pressures:

- Deforestation for plantations (tea, coffee, rubber)

- Quarrying and mining (notably Kudremukh)

- Linear intrusions: roads, railways, powerlines

- Hydropower projects (Sharavathi Valley, Athirappilly proposal)

- Urban expansion around hill stations

- Tourism pressure leading to waste, habitat fragmentation

- Climate change leading to:

- altered monsoon intensity

- increased landslides (Kerala 2018, 2019, 2021)

- loss of endemic species

- Human–wildlife conflict (elephants, leopards in Wayanad, Coorg)

WGEEP (Gadgil Committee) & Kasturirangan Committee

WGEEP – Madhav Gadgil Committee (2011)

Recommended:

- Classifying entire Western Ghats as Ecologically Sensitive Area (ESA)

- Three-tier zonation: ESZ I, II, III

- Strict regulation of mining, polluting industries, dams

- Democratic, decentralised conservation involving Gram Sabhas

State Opposition

- Concerns over restrictions on development

- Fear of affecting livelihoods, plantations, townships

Kasturirangan Committee (2013)

More lenient, politically feasible approach:

- Identified 37% of Western Ghats as ESA (vs. 64% by WGEEP)

- Focused on core natural landscapes

- Excluded plantations, settlements

Current Status

- Ongoing negotiations between Centre and states

- ESA notifications partially implemented

- Still a contentious policy area

Conservation Measures

- Project Tiger reserves: Bandipur, Periyar, Kalakad–Mundanthurai

- Eco-sensitive zones (ESZs) around PAs

- Forest restoration programs in Nilgiris, Western Karnataka

- Community-led conservation (sacred groves, forest councils)

- Sustainable tourism models in Kodagu, Wayanad

- Biodiversity monitoring through citizen science

Case Studies

1. Silent Valley Movement (Kerala)

- 1970s–80s people’s movement opposing hydropower project.

- Saved one of the last primary evergreen forests in India.

- Led to the creation of Silent Valley National Park (1984).

2. Kudremukh Mining Issue

- Iron ore mining degraded shola forests and Bhadra river catchment.

- Supreme Court ordered closure (2005).

- Area now under ecological recovery.

3. Nilgiri Tahr Conservation

- Species population recovering due to protection in Eravikulam NP.

- Tamil Nadu’s Project Nilgiri Tahr expanding conservation measures.

4. Wayanad Human–Wildlife Conflict

- Habitat fragmentation leads to elephant and leopard encounters.

- Solutions: corridor restoration, compensation schemes, early warning systems.

5. Shola Forest Restoration

- Scientific restoration underway in Nilgiris using native species.

- Helps revive hydrological functions and biodiversity.

Conclusion

The Western Ghats are not merely a mountain chain—they are India’s ecological heart, shaping monsoons, sustaining rivers, nurturing biodiversity, and supporting millions of people. But rapid development threatens their stability. The challenge is to balance ecology and economics, ensuring that development is sustainable, inclusive, and scientifically informed.

Preserving the Western Ghats is not only an environmental priority—it is critical for India’s long-term water security, climate resilience, and ecological future.

FAQs on Western Ghats

1. Why are the Western Ghats important for India’s ecology?

The Western Ghats regulate the southwest monsoon, host diverse ecosystems, and support major river systems. They are one of the world’s eight “hottest” biodiversity hotspots and play a critical role in carbon sequestration, freshwater availability, and climate stability.

2. Why did UNESCO declare the Western Ghats a World Heritage Site?

Because of their extremely high levels of endemism, ecological sensitivity, and rich evolutionary history. The Western Ghats contain rare habitats such as shola forests, Myristica swamps and many critically endangered species.

3. Which states are covered by the Western Ghats?

They extend through Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

4. What is the role of the Western Ghats in monsoon rainfall?

They form a major orographic barrier, forcing the southwest monsoon winds to ascend, causing heavy rainfall on the windward side and a rain shadow on the leeward Deccan Plateau.

5. What are the major environmental threats to the Western Ghats?

Key challenges include deforestation, mining, infrastructure expansion, hydropower projects, climate change, and unregulated tourism.

6. What are the main biodiversity hotspots within the Western Ghats?

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Agasthyamalai Biosphere Reserve, Silent Valley, Periyar, and Eravikulam National Park are among the richest habitats.

7. Why was the Gadgil Committee report controversial?

Its recommendation to declare 64% of the Western Ghats as Eco-Sensitive Zones faced opposition from states due to concerns over restrictions on development and livelihoods.

8. Which major rivers originate from the Western Ghats?

Godavari tributaries, Krishna, Tungabhadra, Kaveri, Sharavathi, Mandovi, Netravati, and others originate from the Ghats.

9. What is the significance of the Palghat Gap?

It is the largest discontinuity in the Western Ghats, facilitating movement of people, species migration, and influencing regional climate.

10. How can the Western Ghats be conserved effectively?

Effective conservation needs community-centric approaches, strict regulation of ESZs, habitat restoration, monitoring of tourism, and integration of climate-resilient policies.