Parliament

The Parliament is the legislative organ of the Union Government. It has been given a pre-eminent and central position in the Indian democratic political system due to adoption of the parliamentary form of government, also known as ‘Westminster’ model of government.

Parliament is the legislative organ of the union government, the other two are Executive and Judiciary. Adoption of “Parliamentary form of government” gives pivotal position to parliament in Indian democratic system. A genuine democracy is inconceivable without a representative, efficient and effective legislature. The legislature also helps people in holding the representatives accountable. This is indeed, the very basis of representative democracy. Law-making is but one of the functions of the legislature. It is the centre of all democratic political processes. Legislature is the most representative of all organs of government. The sheer presence of members of diverse social backgrounds makes the legislatures more representative and potentially more responsive to people’s expectations.

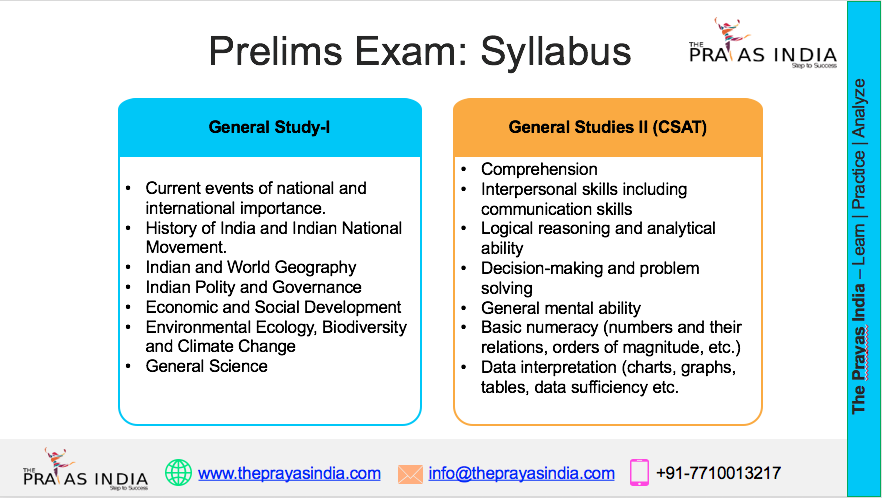

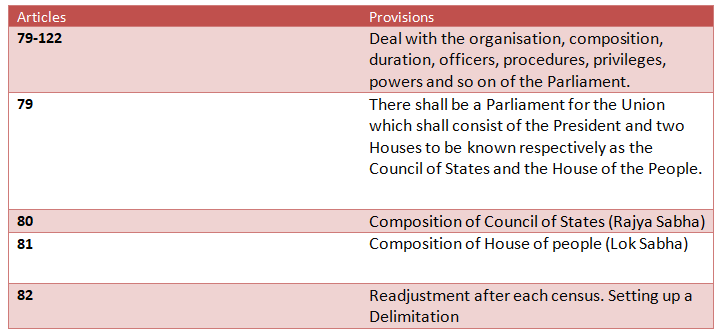

Constitutional Provisions

Organisation of the Parliament

The Parliament consists of three parts i.e., the President, the Council of States and the House of the People. The Rajya Sabha is the upper house that represents the states and union territories of India and the Lok Sabha is the lower house that represents the people of India as a whole. The President of India is not a member of either house of Parliament oand does not sit in the Parliament to attend its meetings, he is an integral part of the Parliament. It is because a bill passed by both the houses of Parliament cannot become law without the President’s assent. He summons and pro-rogues both the houses, dissolves the Lok Sabha, addresses both the houses and issues ordinances when they are not in session. The Parliamentary form of government emphasises on the interdependence between the legislative and executive organs.

Composition of the two Houses

Composition of Rajya Sabha

Maximum strength of the Rajya Sabha is fixed at 250 (238 Members elected indirectly and 12 nominated by the President)

Fourth Schedule of the Constitution Allocation of seats in the Rajya Sabha to the States and Union Territories.

- Total member strength – 245

- Representatives of the States – 229

- Representatives of the Union Territories – 4

- Members nominated by the president – 12

Representatives of states in the Rajya Sabha are elected by the elected members of state legislative assemblies. Method of election:System of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote. The seats are allotted to the states in the Rajya Sabha on the basis of population. India does not have equal representation to the states in Rajya Sabha. In The USA all states are given equal representation in the Senate irrespective of their population. The representatives of each UTs in the Rajya Sabha are indirectly elected by members of an electoral college specially constituted for the purpose. Method of election:- Through a System of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote. Only Delhi, Puducherry and Jammu & Kashmir have representation in Rajya Sabha (total nine union territories). The other six UTs have too small populations to have any representative in the Rajya Sabha. 12 members nominated by President to the Rajya Sabha from people who have special knowledge or practical experience in art, literature, science and social service. Rationale behind provision – to provide eminent persons a place in the Rajya Sabha without going through the process of election. Unlike India, American Senate has no nominated members.

Composition of Lok Sabha

- Maximum strength of the Lok Sabha is fixed at 552.

- Representatives of the States and UTs (elected indirectly)

- Total = 530+20

- Members nominated by the President :- 2 (From Anglo-Indian community)

- Total member strength – 543

- Representatives of the States – 530

- Representatives of the Union Territories – 13

According to Art. 366 (2) Anglo Indian – A person whose father or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent but who is domiciled within the territory of India and is or was born within such territory of parents habitually resident therein and not merely established there for temporary purposes. 61st Constitutional Amendment Act, 1988 – The voting age was reduced from 21 to 18 years. The representatives of states in the Lok Sabha are directly elected by the people from the territorial constituencies in the states. The election is based on the principle of universal adult franchise. Eligible age for every Indian citizen to vote is 18 year. The Constitution has empowered the Parliament to prescribe the manner of choosing the representatives of the UTs in the Lok Sabha. Parliament enacted UTs (Direct Election to the House of the People) Act, 1965, by which the members of Lok Sabha from the UTs are also chosen by direct election. Two Anglo-Indian(Art. 331) community members nominated by the president if the community is not adequately represented in the Lok Sabha. Originally, this provision was to operate till 1960 but has been extended till 2020 by the 95th Amendment Act, 2009. In current 17th Lok Sabha, no member has been nominated from the Anglo-Indian community. Two Anglo-Indian(Art. 331) community members nominated by the president if the community is not adequately represented in the Lok Sabha. Originally, this provision was to operate till 1960 but has been extended till 2020 by the 95th Amendment Act, 2009.

System of Elections to Lok Sabha

Territorial Constituencies

For holding direct elections to the Lok Sabha, each state is divided into territorial constituencies. In this respect, the Constitution provides following two provisions:

- Each state is allotted a number of seats in the Lok Sabha in such a manner that the ratio between that number and its population (preceding census) is the same for all states. However, this provision does not apply to a state having a population of less than six millions.

- Each state is divided into territorial constituencies in such a manner that the ratio between the population (preceding census)of each constituency and the number of seats allotted to it is the same throughout the state.

The Constitution ensures that there is uniformity of the representation in two respects.

- Between the different states

- Between the different constituencies in the same state.

After every census, a readjustment is to be made in allocation of seats in the Lok Sabha to the states. Division of each state into territorial constituencies. Parliament is empowered to determine the authority and the manner in which it is to be made. Accordingly, the Parliament has enacted the Delimitation Commission Acts in 1952, 1962, 1972 and 2002 for this purpose. 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act , 1976 froze the allocation of seats in the Lok Sabha to the states and the division of each state into territorial constituencies till the year 2000 at the 1971 level. Objective for freezing was to encourage population limiting measures. 84th CAA 2001 banned readjustment of seats that was extended for another 25 years (up to year 2026). Also now the readjustment and rationalisation of territorial constituencies to be done on the basis of 1991 census. 87th Constitution Amendment Act, 2003 Provided for the delimitation of constituencies on the basis of 2001 census and not 1991 census.

The Constitution has abandoned the system of communal representation. It provides for the reservation of seats for SC and ST in the Lok Sabha on the basis of population ratios. Originally, this reservation was to operate for ten years (up to 1960), but it has been extended continuously since then by 10 years each time. Now, under the 104th Amendment Act of 2019, this reservation is to last until 2030. Though seats are reserved for SCs and STs, they are elected by all the voters in a constituency, without any separate electorate. However, members of SCs and STs are also not debarred from contesting a general (non-reserved) seat.

Membership of Parliament

Qualifications:

Rajya Sabha:

S/He should be a citizen of India and at least 30 years of age. S/He should make an oath or affirmation stating that s/he will bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India. According to the Representation of People’s Act 1951, s/he should be registered as a voter in the State from which s/he is seeking election to the Rajya Sabha. However, in 2003, a provision was made declaring, any Indian citizen can contest the Rajya Sabha elections irrespective of the State in which s/he resides.

Lok Sabha:

S/He should be not less than 25 years of age. S/He should declare through an oath or affirmation that s/he has true faith and allegiance in the Constitution and that a/he will uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India. S/He must possess such other qualifications as may be laid down by the Parliament by law and must be registered as a voter in any constituency in India. Person contesting from the reserved seat should belong to the Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe as the case may be.

Disqualifications:

On Constitutional Grounds:

If s/he holds any office of profit under the Union or state government (except that of a minister or any other office exempted by Parliament). If s/he is of unsound mind and stands so declared by a court. If s/he is an undischarged insolvent. If s/he is not (or not anymore) a citizen of India. If s/he is disqualified under any law made by Parliament. On Statutory Grounds, Representation of People’s Act 1951 – Found guilty of certain election offences/corrupt practices in the elections. Convicted for any offence resulting in imprisonment for two or more years (detention under a preventive detention law is not a disqualification). Has been dismissed from government service for corruption or disloyalty to the State. Convicted for promoting enmity between different groups or for the offence of bribery. Punished for preaching and practising social crimes such as untouchability, dowry and sati.

Vacating of Seats

In the following cases, a member of Parliament vacates his seat.

- Double Membership: A person cannot be a member of both Houses of Parliament at the same time. Thus, the Representation of People Act (1951) provides for the following:

(a) If a person is elected to both the Houses of Parliament, he must intimate within 10 days in which House he desires to serve. In default of such intimation, his seat in the Rajya Sabha becomes vacant.

(b) If a sitting member of one House is also elected to the other House, his seat in the first House becomes vacant.

(c) If a person is elected to two seats in a House, he should exercise his option for one.

Otherwise, both seats become vacant. Similarly, a person cannot be a member of both the Parliament and the state legislature at the same time. If a person is so elected, his seat in Parliament becomes vacant if he does not resign his seat in the state legislature within 14 days9.

- Disqualification: If a member of Parliament becomes subject to any of the disqualifications specified in the Constitution, his seat becomes vacant. Here, the list of disqualifications also include the disqualification on the grounds of defection under the provisions of the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution.

- Resignation: A member may resign his seat by writing to the Chairman of Rajya Sabha or Speaker of Lok Sabha, as the case may be. The seat falls vacant when the resignation is accepted. However, the Chairman/Speaker may not accept the resignation if he is satisfied that it is not voluntary or genuine.

- Absence: A House can declare the seat of a member vacant if he is absent from all its meetings for a period of sixty days without its permission. In computing the period of sixty days, no account shall be taken of any period during which the House is prorogued or adjourned for more than four consecutive days.

- Other cases: A member has to vacate his seat in the Parliament:

(a) if his election is declared void by the court;

(b) if he is expelled by the House;

(c) if he is elected to the office of President or Vice-President; and

(d) if he is appointed to the office of governor of a state.

If a disqualified person is elected to the Parliament, the Constitution lays down no procedure to declare the election void. This matter is dealt by the Representation of the People Act (1951), which enables the high court to declare an election void if a disqualified candidate is elected. The aggrieved party can appeal to the Supreme Court against the order of the high court in this regard.

Tenure:

Rajya Sabha: Every member of Rajya Sabha enjoys a safe tenure of six years. One-third of its members retire after every two years. They are entitled to contest again for the membership.

Lok Sabha: The normal term of Lok Sabha is five years. But the President, on the advice of the Council of Ministers, may dissolve it before the expiry of five years. In the case of national emergency, its term can be extended for one year at a time. But it will not exceed six months after the emergency is over.

Officials:

Rajya Sabha: The Vice-President of India is the ex-officio Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. S/He presides over the meetings of Rajya Sabha. In his absence the Deputy Chairman (elected by its members from amongst themselves) presides over the meeting of the House.

Lok Sabha: The Presiding officer of Lok Sabha is known as Speaker. S/He remains the Speaker even after Lok Sabha is dissolved till the next House elects a new Speaker in her/his place. In the speaker’s absence, a Deputy Speaker (elected by the House) presides over the meetings.

Oath or Affirmation

Every member of either House of Parliament, before taking his seat in the House, has to make and subscribe to an oath or affirmation before the President or some person appointed by him for this purpose. In his oath or affirmation, a member of Parliament swears:

- to bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India;

- to uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India; and

- to faithfully discharge the duty upon which he is about to enter.

Unless a member takes the oath, he cannot vote and participate in the proceedings of the House and does not become eligible to parliamentary privileges and immunities.

A person is liable to a penalty of Rs 500 for each day he sits or votes as a member in a House in the following conditions:

- Before taking and subscribing to the prescribed oath or affirmation; or

- When he knows that he is not qualified or that he is disqualified for its membership; or

- When he knows that he is prohibited from sitting or voting in the House by virtue of any parliamentary law.

Salaries and Allowances:

Members of either House of Parliament are entitled to receive such salaries and allowances as may be determined by Parliament, and there is no provision of pension in the Constitution. However, Parliament has provided pension to the members. In 1954, the Parliament enacted the Salaries, Allowances and Pension of Members of Parliament Act. In 2010, the Parliament increased the salary of members from Rs. 16,000 to Rs. 50,000 per month, the constituency allowance from Rs. 20,000 to Rs. 45,000 per month, the daily allowance from Rs. 1,000 to Rs. 2,000 for five years and office expenses allowance from Rs. 20,000 to Rs. 45,000 per month. From 1976, the members are also entitled to a pension on a graduated scale for each five-year-term as members of either House of Parliament. Besides, they are provided with travelling facilities, free accommodation, telephone, vehicle advance, medical facilities and so on. The salaries and allowances of the Speaker of Lok Sabha and the Chairman of Rajya Sabha are also determined by Parliament. They are charged on the Consolidated Fund of India and thus are not subject to the annual vote of Parliament. In 1953, the Parliament enacted the Salaries and Allowances of Officers of Parliament Act. Under this Act, the Parliament has fixed the salaries as well as allowances of both the Speaker and the Chairman.

Presiding Officers of Parliament

Speaker:

Election and Tenure

The Speaker is elected by the Lok Sabha from amongst its members (as soon as may be, after its first sitting). Whenever the office of the Speaker falls vacant, the Lok Sabha elects another member to fill the vacancy. The date of election of the Speaker is fixed by the President.

Usually, the Speaker remains in office during the life of the Lok Sabha. However, he has to vacate his office earlier in any of the following three cases:

- if he ceases to be a member of the Lok Sabha;

- if he resigns by writing to the Deputy Speaker; and

- if he is removed by a resolution passed by a majority of all the members of the Lok Sabha. Such a resolution can be moved only after giving 14 days’ advanced notice.

When a resolution for the removal of the Speaker is under consideration of the House, he cannot preside at the sitting of the House, though he may be present. However, he can speak and take part in the proceedings of the House at such a time and vote in the first instance, though not in the case of an equality of votes.

It should be noted here that, whenever the Lok Sabha is dissolved, the Speaker does not vacate his office and continues till the newly- elected Lok Sabha meets.

Role, Powers and Functions

The Speaker is the head of the Lok Sabha, and its representative. He is the guardian of powers and privileges of the members, the House as a whole and its committees. He is the principal spokesman of the House, and his decision in all Parliamentary matters is final. He is thus much more than merely the presiding officer of the Lok Sabha. In these capacities, he is vested with vast, varied and vital responsibilities and enjoys great honour, high dignity and supreme authority within the House.

The Speaker of the Lok Sabha derives his powers and duties from three sources, that is, the Constitution of India, the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business of Lok Sabha, and Parliamentary Conventions (residuary powers that are unwritten or unspecified in the Rules).

Altogether, he has the following powers and duties:

- He maintains order and decorum in the House for conducting its business and regulating its proceedings. This is his primary responsibility and he has final power in this regard.

- He is the final interpreter of the provisions of (a) the Constitution of India, (b) the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business of Lok Sabha, and (c) the parliamentary precedents, within the House.

- He adjourns the House or suspends the meeting in absence of a quorum. The quorum to constitute a meeting of the House is one-tenth of the total strength of the House.

- He does not vote in the first instance. But he can exercise a casting vote in the case of a tie. In other words, only when the House is divided equally on any question, the Speaker is entitled to vote. Such vote is called casting vote, and its purpose is to resolve a deadlock.

- He presides over a joint setting of the two Houses of Parliament. Such a sitting is summoned by the President to settle a deadlock between the two Houses on a bill.

- He can allow a ‘secret’ sitting of the House at the request of the Leader of the House. When the House sits in secret, no stranger can be present in the chamber, lobby or galleries except with the permission of the Speaker.

- He decides whether a bill is a money bill or not and his decision on this question is final. When a money bill is transmitted to the Rajya Sabha for recommendation and presented to the President for assent, the Speaker endorses on the bill his certificate that it is a money bill.

- He decides the questions of disqualification of a member of the Lok Sabha, arising on the ground of defection under the provisions of the Tenth Schedule. In 1992, the Supreme Court ruled that the decision of the Speaker in this regard is subject to judicial review. (Kihota Hollohan Vs. Zachilhu (1992).)

- He acts as the ex-officio chairman of the Indian Parliamentary Group of the Inter- Parliamentary Union. He also acts as the ex-officio chairman of the conference of presiding officers of legislative bodies in the country.

- He appoints the chairman of all the parliamentary committees of the Lok Sabha and supervises their functioning. He himself is the chairman of the Business Advisory Committee, the Rules Committee and the General-Purpose Committee.

Independence and Impartiality of Speaker

impartiality is regarded as an indispensable condition of the office of the Speaker, who is the guardian of the powers and privileges of the House and not of the political party with whose support he might have been elected to the office. It is not possible for him to maintain order in the House unless he enjoys the confidence of the minority parties by safeguarding their rights and privileges. The following provisions ensure the independence and impartiality of the office of the Speaker:

- He is provided with a security of tenure. He can be removed only by a resolution passed by the Lok Sabha by an absolute majority (i.e., a majority of the total members of the House) and not by an ordinary majority (i.e., a majority of the members present and voting in the House).

- This motion of removal can be considered and discussed only when it has the support of at least 50 members.

- His salaries and allowances are fixed by Parliament. They are charged on the Consolidated Fund of India and thus are not subject to the annual vote of Parliament.

- His work and conduct cannot be discussed and criticized in the Lok Sabha except on a substantive motion.

- His powers of regulating procedure or conducting business or maintaining order in the House are not subject to the jurisdiction of any Court.

- He cannot vote in the first instance. He can only exercise a casting vote in the event of a tie. This makes the position of Speaker impartial.

- He is given a very high position in the order of precedence. He is placed at seventh rank, along with the Chief Justice of India. This means, he has a higher rank than all cabinet ministers, except the Prime Minister or Deputy Prime Minister.

In Britain, the Speaker is strictly a non-party man. There is a convention that the Speaker has to resign from his party and remain politically neutral. This healthy convention is not fully established in India where the Speaker does not resign from the membership of his party on his election to the exalted office

Deputy Speaker

Like the Speaker, the Deputy Speaker is also elected by the Lok Sabha itself from amongst its members. He is elected after the election of the Speaker has taken place. The date of election of the Deputy Speaker is fixed by the Speaker. Whenever the office of the Deputy Speaker falls vacant, the Lok Sabha elects another member to fill the vacancy. Like the Speaker, the Deputy Speaker remains in office usually during the life of the Lok Sabha. However, he may vacate his office earlier in any of the following three cases: 1. if he ceases to be a member of the Lok Sabha; 2. if he resigns by writing to the Speaker; and 3. if he is removed by a resolution passed by a majority of all the members of the Lok Sabha. Such a resolution can be moved only after giving 14 days’ advance notice. The Deputy Speaker performs the duties of the Speaker’s office when it is vacant. He also acts as the Speaker when the latter is absent from the sitting of the House. In both the cases, he assumes all the powers of the Speaker. He also presides over the joint sitting of both the Houses of Parliament, in case the Speaker is absent from such a sitting. It should be noted here that the Deputy Speaker is not subordinate to the Speaker. He is directly responsible to the House. The Deputy Speaker has one special privilege, that is, whenever he is appointed as a member of a parliamentary committee, he automatically becomes its chairman. Like the Speaker, the Deputy Speaker, while presiding over the House, cannot vote in the first instance; he can only exercise a casting vote in the case of a tie. Further, when a resolution for the removal of the Deputy Speaker is under consideration of the House, he cannot preside at the sitting of the House, though he may be present. When the Speaker presides over the House, the Deputy Speaker is like any other ordinary member of the House. He can speak in the House, participate in its proceedings and vote on any question before the House. The Deputy Speaker is entitled to a regular salary and allowance fixed by Parliament, and charged on the Consolidated Fund of India. Up to the 10th Lok Sabha, both the Speaker and the Deputy Speaker were usually from the ruling party. Since the 11th Lok Sabha, there has been a consensus that the Speaker comes from the ruling party (or ruling alliance) and the post of Deputy Speaker goes to the main opposition party. The Speaker and the Deputy Speaker, while assuming their offices, do not make and subscribe any separate oath or affirmation. The institutions of Speaker and Deputy Speaker originated in India in 1921 under the provisions of the Government of India Act of 1919 (Montague–Chelmsford Reforms). At that time, the Speaker and the Deputy Speaker were called the President and Deputy President respectively and the same nomenclature continued till 1947. Before 1921, the Governor- General of India used to preside over the meetings of the Central Legislative Council. In 1921, the Frederick Whyte and Sachidanand Sinha were appointed by the Governor-General of India as the first Speaker and the first Deputy Speaker (respectively) of the central legislative assembly. In 1925, Vithalbhai J. Patel became the first Indian and the first elected Speaker of the central legislative assembly. The Government of India Act of 1935 changed the nomenclatures of President and Deputy President of the Central Legislative Assembly to the Speaker and Deputy Speaker respectively. However, the old nomenclature continued till 1947 as the federal part of the 1935 Act was not implemented. G V Mavalankar and Ananthasayanam Ayyangar had the distinction of being the first Speaker and the first Deputy Speaker (respectively) of the Lok Sabha. G V Mavalankar also held the post of Speaker in the Constituent Assembly (Legislative) as well as the provisional Parliament. He held the post of Speaker of Lok Sabha continuously for one decade from 1946 to 1956.

Panel of Chairpersons of Lok Sabha

Under the Rules of Lok Sabha, the Speaker nominates from amongst the members a panel of not more than ten chairpersons. Any of them can preside over the House in the absence of the Speaker or the Deputy Speaker. He has the same powers as the Speaker when so presiding. He holds office until a new panel of chairpersons is nominated. When a member of the panel of chairpersons is also not present, any other person as determined by House acts as the Speaker. It must be emphasised here that a member of the panel of chairpersons cannot preside over the House, when the office of the Speaker or the Deputy Speaker is vacant. During such time, the Speaker’s duties are to be performed by such member of the House as the President may appoint for the purpose. The elections are held, as soon as possible, to fill the vacant posts.

Speaker Pro Tem:

As provided by the Constitution, the Speaker of the last Lok Sabha vacates his office immediately before the first meeting of the newly- elected Lok Sabha. Therefore, the President appoints a member of the Lok Sabha as the Speaker Pro Tem. Usually, the seniormost member is selected for this. The President himself administers oath to the Speaker Pro Tem. The Speaker Pro Tem has all the powers of the Speaker. He presides over the first sitting of the newly-elected Lok Sabha. His main duty is to administer oath to the new members. He also enables the House to elect the new Speaker. When the new Speaker is elected by the House, the office of the Speaker Pro Tem ceases to exist. Hence, this office is a temporary office, existing for a few days.

Chairman of Rajya Sabha:

The presiding officer of the Rajya Sabha is known as the Chairman. The vice-president of India is the ex-officio Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. During any period when the Vice-President acts as President or discharges the functions of the President, he does not perform the duties of the office of the Chairman of Rajya Sabha. The Chairman of the Rajya Sabha can be removed from his office only if he is removed from the office of the Vice-President. As a presiding officer, the powers and functions of the Chairman in the Rajya Sabha are similar to those of the Speaker in the Lok Sabha. However, the Speaker has two special powers which are not enjoyed by the Chairman: 1. The Speaker decides whether a bill is a money bill or not and his decision on this question is final. 2. The Speaker presides over a joint sitting of two Houses of Parliament. Unlike the Speaker (who is a member of the House), the Chairman is not a member of the House. But like the Speaker, the Chairman also cannot vote in the first instance. He too can cast a vote in the case of an equality of votes. The Vice-President cannot preside over a sitting of the Rajya Sabha as its Chairman when a resolution for his removal is under consideration. However, he can be present and speak in the House and can take part in its proceedings, without voting, even at such a time (while the Speaker can vote in the first instance when a resolution for his removal is under consideration of the Lok Sabha). As in case of the Speaker, the salaries and allowances of the Chairman are also fixed by the Parliament. They are charged on the Consolidated Fund of India and thus are not subject to the annual vote of Parliament. During any period when the Vice-President acts as President or discharges the functions of the President, he is not entitled to any salary or allowance payable to the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. But he is paid the salary and allowance of the President during such a time.

Deputy Chairman of Rajya Sabha:

The Deputy Chairman is elected by the Rajya Sabha itself from amongst its members. Whenever the office of the Deputy Chairman falls vacant, the Rajya Sabha elects another member to fill the vacancy. The Deputy Chairman vacates his office in any of the following three cases: 1. if he ceases to be a member of the Rajya Sabha; 2. if he resigns by writing to the Chairman; and 3. if he is removed by a resolution passed by a majority of all the members of the Rajya Sabha. Such a resolution can be moved only after giving 14 days’ advance notice. The Deputy Chairman performs the duties of the Chairman’s office when it is vacant or when the Vice-President acts as President or discharges the functions of the President. He also acts as the Chairman when the latter is absent from the sitting of the House. In both the cases, he has all the powers of the Chairman. It should be emphasised here that the Deputy Chairman is not subordinate to the Chairman. He is directly responsible to the Rajya Sabha. Like the Chairman, the Deputy Chairman, while presiding over the House, cannot vote in the first instance; he can only exercise a casting vote in the case of a tie. Further, when a resolution for the removal of the Deputy Chairman is under consideration of the House, he cannot preside over a sitting of the House, though he may be present. When the Chairman presides over the House, the Deputy Chairman is like any other ordinary member of the House. He can speak in the House, participate in its proceedings and vote on any question before the House. Like the Chairman, the Deputy Chairman is also entitled to a regular salary and allowance. They are fixed by Parliament and are charged on the Consolidated Fund of India.

Panel of Vice-Chairpersons of Rajya Sabha:

Under the Rules of Rajya Sabha, the Chairman nominates from amongst the members a panel of vice chairpersons. Any one of them can preside over the House in the absence of the Chairman or the Deputy Chairman. He has the same powers as the Chairman when so presiding. He holds office until a new panel of vice-chairpersons is nominated. When a member of the panel of vice-chairpersons is also not present, any other person as determined by the House acts as the Chairman. It must be emphasised here that a member of the panel of vice-chairpersons cannot preside over the House, when the office of the Chairman or the Deputy Chairman is vacant. During such time, the Chairman’s duties are to be performed by such member of the House as the president may appoint for the purpose. The elections are held, as soon as possible, to fill the vacant posts.

Secretariat of Parliament:

Each House of Parliament has separate secretarial staff of its own, though there can be some posts common to both the Houses. Their recruitment and service conditions are regulated by Parliament. The secretariat of each House is headed by a secretary-general. He is a permanent officer and is appointed by the presiding officer of the House.

Leaders of Parliament

Leader of the House:

Under the Rules of Lok Sabha, the ‘Leader of the House’ means the prime minister, if he is a member of the Lok Sabha, or a minister who is a member of the Lok Sabha and is nominated by the prime minister to function as the Leader of the House. There is also a ‘Leader of the House’ in the Rajya Sabha. He is a minister and a member of the Rajya Sabha and is nominated by the prime minister to function as such. The leader of the house in either House is an important functionary and exercises direct influence on the conduct of business. He can also nominate a deputy leader of the House. The same functionary in USA is known as the ‘majority leader’.

Leader of the Opposition:

In each House of Parliament, there is the ‘Leader of the Opposition’. The leader of the largest Opposition party having not less than one-tenth seats of the total strength of the House is recognized as the leader of the Opposition in that House. In a parliamentary system of government, the leader of the opposition has a significant role to play. His main functions are to provide a constructive criticism of the policies of the government and to provide an alternative government. Therefore, the leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha were accorded statutory recognition in 1977. They are also entitled to the salary, allowances and other facilities equivalent to that of a cabinet minister. It was in 1969 that an official leader of the opposition was recognised for the first time. The same functionary in USA is known as the ‘minority leader’.

The British political system has an unique institution called the ‘Shadow Cabinet’. It is formed by the Opposition party to balance the ruling cabinet and to prepare its members for future ministerial offices. In this shadow cabinet, almost every member in the ruling cabinet is ‘shadowed’ by a corresponding member in the opposition cabinet. This shadow cabinet serves as the ‘alternate cabinet’ if there is change of government. That is why Ivor Jennings described the leader of Opposition as the ‘alternative Prime Minister’. He enjoys the status of a minister and is paid by the government

Whip:

Though the offices of the leader of the House and the leader of the Opposition are not mentioned in the Constitution of India, they are mentioned in the Rules of the House and Parliamentary Statute respectively. The office of ‘whip’, on the other hand, is mentioned neither in the Constitution of India nor in the Rules of the House nor in a Parliamentary Statute. It is based on the conventions of the parliamentary government.

Every political party, whether ruling or Opposition has its own whip in the Parliament. He is appointed by the political party to serve as an assistant floor leader. He is charged with the responsibility of ensuring the attendance of his party members in large numbers and securing their support in favor of or against a particular issue. He regulates and monitors their behavior in the Parliament. The members are supposed to follow the directives given by the whip. Otherwise, disciplinary action can be taken.

Sessions of Parliament

There are usually three sessions in a year, viz, 1. Budget Session (February to May); 2. Monsoon Session (July to September); and 3. Winter Session (November to December). A ‘session’ of Parliament is the period spanning between the first sitting of a House and its prorogation (or dissolution in the case of the Lok Sabha). During a session, the House meets every day to transact business. The period spanning between the prorogation of a House and its reassembly in a new session is called ‘recess’.

Summoning

The president from time to time summons each House of Parliament to meet. But, the maximum gap between two sessions of Parliament cannot be more than six months. In other words, the Parliament should meet at least twice a year. A session of Parliament consists of many meetings. Each meeting of a day consists of two sittings, that is, a morning sitting from 11 am to 1 pm and post-lunch sitting from 2 pm to 6 pm. A sitting of Parliament can be terminated by adjournment or adjournment sine die or prorogation or dissolution (in the case of the Lok Sabha).

Adjournment

An adjournment suspends the work in a sitting for a specified time, which may be hours, days or weeks. Adjournment Sine Die Adjournment sine die means terminating a sitting of Parliament for an indefinite period. In other words, when the House is adjourned without naming a day for reassembly, it is called adjournment sine die. The power of adjournment as well as adjournment sine die lies with the presiding officer of the House. He can also call a sitting of the House before the date or time to which it has been adjourned or at any time after the House has been adjourned sine die. Prorogation The presiding officer (Speaker or Chairman) declares the House adjourned sine die, when the business of a session is completed. Within the next few days, the President issues a notification for prorogation of the session. However, the President can also prorogue the House while in session.

Dissolution

Rajya Sabha, being a permanent House, is not subject to dissolution. Only the Lok Sabha is subject to dissolution. Unlike a prorogation, a dissolution ends the very life of the existing House, and a new House is constituted after general elections are held. The dissolution of the Lok Sabha may take place in either of two ways: 1. Automatic dissolution, that is, on the expiry of its tenure of five years or the terms as extended during a national emergency; or 2. Whenever the President decides to dissolve the House, which he is authorized to do. Once the Lok Sabha is dissolved before the completion of its normal tenure, the dissolution is irrevocable. When the Lok Sabha is dissolved, all business including bills, motions, resolutions, notices, petitions and so on pending before it or its committees lapse. They (to be pursued further) must be reintroduced in the newly-constituted Lok Sabha. However, some pending bills and all pending assurances that are to be examined by the Committee on Government Assurances do not lapse on the dissolution of the Lok Sabha. The position with respect to lapsing of bills is as follows: 1. A bill pending in the Lok Sabha lapses (whether originating in the Lok Sabha or transmitted to it by the Rajya Sabha). 2. A bill passed by the Lok Sabha but pending in the Rajya Sabha lapses. 3. A bill not passed by the two Houses due to disagreement and if the president has notified the holding of a joint sitting before the dissolution of Lok Sabha, does not lapse. 4. A bill pending in the Rajya Sabha but not passed by the Lok Sabha does not lapse. 5. A bill passed by both Houses but pending assent of the president does not lapse. 6. A bill passed by both Houses but returned by the president for reconsideration of Houses does not lapse.

Under Article 107 (3) of the Constitution, a bill pending in Parliament shall not lapse by reason of the prorogation of the Houses. Under Rule 336 of the Lok Sabha, a motion, resolution or an amendment, which has been moved and is pending in the House, shall not lapse by reason only of the prorogation of the House.

Quorum

Quorum is the minimum number of members required to be present in the House before it can transact any business. It is one-tenth of the total number of members in each House including the presiding officer. It means that there must be at least 55 members present in the Lok Sabha and 25 members present in the Rajya Sabha, if any business is to be conducted. If there is no quorum during a meeting of the House, it is the duty of the presiding officer either to adjourn the House or to suspend the meeting until there is a quorum.

Lame Duck Session

It refers to the last session of the existing Lok Sabha, after a new Lok Sabha has been elected. Those members of the existing Lok Sabha who could not get re-elected to the new Lok Sabha are called lame-ducks.

Voting in House

All matters at any sitting of either House or joint sitting of both the Houses are decided by a majority of votes of the members present and voting, excluding the presiding officer. Only a few matters, which are specifically mentioned in the Constitution like impeachment of the President, amendment of the Constitution, removal of the presiding officers of the Parliament and so on, require special majority, not ordinary majority.

The presiding officer of a House does not vote in the first instance, but exercises a casting vote in the case of an equality of votes. The proceedings of a House are to be valid irrespective of any unauthorized voting or participation or any vacancy in its membership.

Language in Parliament

The Constitution has declared Hindi and English to be the languages for transacting business in the Parliament. However, the presiding officer can permit a member to address the House in his mother tongue. In both the Houses, arrangements are made for simultaneous translation. Though English was to be discontinued as a floor language after the expiration of fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution (that is, in 1965), the Official Languages Act (1963) allowed English to be continued along with Hindi.

Rights of Ministers and Attorney General

In addition to the members of a House, every minister and the attorney general of India have the right to speak and take part in the proceedings of either House, any joint sitting of both the Houses and any committee of Parliament of which he is a member, without being entitled to vote. There are two reasons underlying this constitutional provision:

- A minister can participate in the proceedings of a House, of which he is not a member. In other words, a minister belonging to the Lok Sabha can participate in the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha and vice-versa.

- A minister, who is not a member of either House, can participate in the proceedings of both the Houses. It should be noted here that a person can remain a minister for six months, without being a member of either House of Parliament.

Devices of Parliamentary Proceeding

Question Hour

First hour, i.e. 11a.m. to 12 a.m. of every parliamentary sitting is slotted for this. During this time, the members ask questions and the ministers usually give answers. The questions are of three kinds, namely, starred, un-starred and short notice. A starred question (distinguished by an asterisk) requires an oral answer and hence supplementary questions can follow. Only 20 questions can be listed for oral answer on a day. An un-starred question, on the other hand, requires a written answer and hence, supplementary questions cannot follow. It Requires a time-period of 10 days. A short notice question is one that is asked by giving a notice of less than ten days. It is answered orally. Each MP can submit a maximum of 10 questions for each day of the Parliament’s sitting when question hour is to take place. The submissions are made 15 days before the date assigned for answer and a paper signed by the MP listing the question must be submitted in the parliamentary notice office.

The privilege of asking starred and unstarred questions are with the members of parliament. There are two different forms for starred and unstarred questions. A question in form meant for starred question is a starred question and question in a form for unstarred question is an unstarred question.

Minimum period of notice for starred/ unstarred question is 10 clear days. The normal period of notice does not apply to Short Notice Questions which relate to matters of urgent public importance. However, a Short Notice Question may only be answered on short notice if so permitted by the Speaker and the Minister concerned is prepared to answer it at shorter notice. A Short Notice Question is taken up for answer immediately after the Question Hour.

Zero Hour

Unlike the question hour, the zero hour is not mentioned in the Rules of Procedure. Thus, it is an informal device available to the members of the Parliament to raise matters without any prior notice.

The zero hour starts immediately after the question hour and lasts until the agenda for the day (i.e., regular business of the House) is taken up. In other words, the time gap between the question hour and the agenda is known as zero hour. It is an Indian innovation in the field of parliamentary procedures and has been in existence since 1962.

Motions

Motion is a procedure device through which the work of the legislature is carried on. It is a proposal by an MP to express his/her opinion. No discussion on a matter of general public importance can take place except on a motion made with the consent of the presiding officer. The House expresses its decisions or opinions on various issues through the adoption or rejection of motions moved by either ministers or private members.

A motion goes through the following four stages:

- Moving of the motion – the member proposing the motion will introduce the motion.

- Proposing the question by the Speaker/Chairman – the Speaker/Chairman allow the motion by admiting it.

- Debate or discussion where permissible – discussions or debates on the matter in the motion are not allowed in all cases; only in a few types of motions debates or discussion are allowed.

- Voting or decision of the house – the matter in the motion is voted on.

All motions fall into three principal categories:

- Substantive Motion

- Substitute Motion

- Subsidiary Motion

Some Important Motions

Closure Motion

It is a motion moved by a member to cut short the debate on a matter before the House. If the motion is approved by the House, debate is stopped forthwith and the matter is put to vote. There are four kinds of closure motions:

- Simple Closure: It is one when a member moves that the ‘matter having been sufficiently discussed be now put to vote’.

- Closure by Compartments: In this case, the clauses of a bill or a lengthy resolution are grouped into parts before the commencement of the debate. The debate covers the part as a whole and the entire part is put to vote.

- Kangaroo Closure: Under this type, only important clauses are taken up for debate and voting and the intervening clauses are skipped over and taken as passed.

- Guillotine Closure: It is one when the undiscussed clauses of a bill or a resolution are also put to vote along with the discussed ones due to want of time (as the time allotted for the discussion is over).

Privilege Motion

It is moved by a member when he feels that a minister has committed a breach of privilege of the House or one or more of its members by withholding facts of a case or by giving wrong or distorted facts. Its purpose is to censure the concerned minister.

Calling Attention Motion

It is introduced in the Parliament by a member with prior permission of the speaker to call the attention of a minister to a matter of urgent public importance, and to seek an authoritative statement from him on that matter. The minister may make a brief statement or ask for the time to make a statement at later hour or date. Like the zero hour, it is also an Indian innovation in the parliamentary procedure and has been in existence since 1954. However, unlike the zero hour, it is mentioned in the Rules of Procedure.

Adjournment Motion

Setting aside normal business of the house for discussing a matter of urgent public importance It is introduced in the Parliament to draw attention of the House to a definite matter of urgent public importance, and needs the support of 50 members to be admitted. As it interrupts the normal business of the House, it is regarded as an extraordinary device. It involves an element of censure against the government and hence Rajya Sabha is not permitted to make use of this device. The discussion on an adjournment motion should last for not less than two hours and thirty minutes.

The right to move a motion for an adjournment of the business of the House is subject to the following restrictions:

- It should raise a matter which is definite, factual, urgent and of public importance;

- It should not cover more than one matter;

- It should be restricted to a specific matter of recent occurrence and should not be framed in general terms;

- It should not raise a question of privilege;

- It should not revive discussion on a matter that has been discussed in the same session;

- It should not deal with any matter that is under adjudication by court; and

- It should not raise any question that can be raised on a distinct motion.

No-Confidence Motion

Article 75 of the Constitution says that the council of ministers shall be collectively responsible to the Lok Sabha. It means that the ministry stays in office so long as it enjoys confidence of the majority of the members of the Lok Sabha. In other words, the Lok Sabha can remove the ministry from office by passing a no-confidence motion. The motion needs the support of 50 members to be admitted.

Censure Motion

A censure motion is different from a no-confidence motion as shown in following table:

| Censure Motion | No confidence Motion |

|---|---|

| It should state the reason of its adoption in Lok Sabha. | Need not state the reason of its adoption in Lok Sabha. |

| It can be moved against an individual minister or a group of ministers of the entire council of ministers. | It can be moved against the entire council of ministers only. |

| It is moved for censuring the council of ministers for specific policies and actions. | It is moved for ascertaining the confidence of Lok Sabha in the council of ministers. |

| If it is passed in Lok Sabha, the council of ministers need not resign from office. | If it is passed in Lok Sabha, the council of ministers must resign from office. |

Censure Motion and No-confidence motion can be introduced only in Lok Sabha.

Motion of Thanks

The first session after each general election and the first session of every fiscal year is addressed by the president. In this address, the president outlines the policies and programmes of the government in the preceding year and ensuing year. This address of the president, which corresponds to the ‘speech from the Throne in Britain’, is discussed in both the Houses of Parliament on a motion called the ‘Motion of Thanks’. At the end of the discussion, the motion is put to vote. This motion must be passed in the House. Otherwise, it amounts to the defeat of the government. This inaugural speech of the president is an occasion available to the members of Parliament to raise discussions and debates to examine and criticise the government and administration for its lapses and failures.

No-Day-Yet-Named Motion

It is a motion that has been admitted by the Speaker but no date has been fixed for its discussion. The Speaker, after considering the state of business in the House and in consultation with the leader of the House or on the recommendation of the Business Advisory Committee, allots a day or days or part of a day for the discussion of such a motion.

Point of Order

A member can raise a point of order when the proceedings of the House do not follow the normal rules of procedure. A point of order should relate to the interpretation or enforcement of the Rules of the House or such articles of the Constitution that regulate the business of the House and should raise a question that is within the cognizance of the Speaker. It is usually raised by an opposition member in order to control the government. It is an extraordinary device as it suspends the proceedings before the House. No debate is allowed on a point of order.

Half-an-Hour Discussion

It is meant for discussing a matter of sufficient public importance, which has been subjected to a lot of debate and the answer to which needs elucidation on a matter of fact. The Speaker can allot three days in a week for such discussions. There is no formal motion or voting before the House.

Short Duration Discussion

It is also known as two-hour discussion as the time allotted for such a discussion should not exceed two hours. The members of the Parliament can raise such discussions on a matter of urgent public importance. The Speaker can allot two days in a week for such discussions. There is neither a formal motion before the house nor voting. This device has been in existence since 1953.

Special Mention

A matter which is not a point of order or which cannot be raised during question hour, half-an hour discussion, short duration discussion or under adjournment motion, calling attention notice or under any rule of the House can be raised under the special mention in the Rajya Sabha. Its equivalent procedural device in the Lok Sabha is known as ‘Notice (Mention) Under Rule 377’.

Resolutions

Procedural device available to members & ministers to raise a discussion in the house on matter of general public interest.

- A resolution is in fact a substantive motion but unlike motions, resolution forms have been provided with the rules concerning both the houses.

- If resolution is passed in form of statute / law, it has the binding effect. But, if it is passed as an expression of opinion, it has only persuasive effect.

- Hence, resolution is a particular type of motion, required to be voted upon, unlike as in case of motion.

- The discussion on a resolution is strictly relevant to and within the scope of the resolution. A member who has moved a resolution or amendment to a resolution cannot withdraw the same except by leave of the House.

Resolutions are classified into three categories:

- Private Member’s Resolution: It is one that is moved by a private member (other than a minister). It is discussed only on alternate Fridays and in the afternoon sitting.

- Government Resolution: It is one that is moved by a minister. It can be taken up any day from Monday to Thursday.

- Statutory Resolution: It can be moved either by a private member or a minister. It is so called because it is always tabled in pursuance of a provision in the Constitution or an Act of Parliament.

Resolutions are different from motions in the following respects:

“All resolutions come in the category of substantive motions, that is to say, every resolution is a particular type of motion. All motions need not necessarily be substantive. Further, all motions are not necessarily put to vote of the House, whereas all the resolutions are required to be voted upon.”

- The difference between a motion and resolution is more of procedure than content, i.e., the content of a resolution and a motion can be the same but the manner in which it is adopted and the decision on the content will differ.

- All resolutions come under the category of substantive motions but all motions are not resolutions.

Youth Parliament:

The scheme of Youth Parliament was started on the recommendation of the Fourth All India Whips Conference. Its objectives are:

- to acquaint the younger generations with practices and procedures of Parliament;

- to imbibe the spirit of discipline and tolerance cultivating character in the minds of youth; and

- to inculcate in the student community the basic values of democracy and to enable them to acquire a proper perspective on the functioning of democratic institutions.

The ministry of parliamentary affairs provides necessary training and encouragement to the states in introducing the scheme.

Legislative Procedure in Parliament

The legislative procedure is identical in both the Houses of Parliament. Every bill has to pass through the same stages in each House. A bill is a proposal for legislation and it becomes an act or law when duly enacted.

Types of Bills in Parliament:

Bills introduced in the Parliament are of two kinds: public bills and private bills (also known as government bills and private members’ bills respectively). Though both are governed by the same general procedure and pass through the same stages in the House, they differ in various respects as shown in following table:

| Public Bill | Private Bill |

|---|---|

| Introduced in the parliament by a minister | Introduced by any member of parliament other than minister |

| It reflects the policies of the government (ruling party) | It reflects the stand of opposition party on public matter. |

| It has greater chance to be approved by parliament. | It has lesser chance to be approved by parliament. |

| Its rejection in the house amounts to the expression of want of parliamentary confidence in the government and may lead to its resignation. | Its resignation by the house has no implication on the parliamentary confidence in the government or its resignation. |

| Its introduction in the house requires 7 days’ notice. | Its introduction in the house requires 1 month’s notice. |

| It is drafted by the concerned department in consultation with the law department. | Its drafting is the responsibility of the member concerned. |

The bills introduced in the Parliament can also be classified into four categories:

- Ordinary Bills: which are concerned with any matter other than financial subjects.

- Money Bills: which are concerned with the financial matters like taxation, public expenditure, etc.

- Financial Bills: which are also concerned with financial matters (but are different from money bills).

- Constitution amendment bills : which are concerned with the amendment of the provisions of the Constitution.

Joint Sitting of two houses

Joint sitting is an extraordinary machinery provided by the Constitution to resolve a deadlock between the two Houses over the passage of a bill. A deadlock is deemed to have taken place under any one of the following three situations after a bill has been passed by one House and transmitted to the other House:

1. if the bill is rejected by the other House; 2. if the Houses have finally disagreed as to the amendments to be made in the bill; or 3. if more than six months have elapsed from the date of the receipt of the bill by the other House without the bill being passed by it.

In the above three situations, the president can summon both the Houses to meet in a joint sitting for the purpose of deliberating and voting on the bill. It must be noted here that the provision of joint sitting is applicable to ordinary bills or financial bills only and not to money bills or Constitutional amendment bills. In the case of a money bill, the Lok Sabha has overriding powers, while a Constitutional amendment bill must be passed by each House separately.

In reckoning the period of six months, no account can be taken of any period during which the other House (to which the bill has been sent) is prorogued or adjourned for more than four consecutive days. If the bill (under dispute) has already lapsed due to the dissolution of the Lok Sabha, no joint sitting can be summoned. But, the joint sitting can be held if the Lok Sabha is dissolved after the President has notified his intention to summon such a sitting (as the bill does not lapse in this case). After the President notifies his intention to summon a joint sitting of the two Houses, none of the Houses can proceed further with the bill.

The Speaker of Lok Sabha presides over a joint sitting of the two Houses and the Deputy Speaker, in his absence. If the Deputy Speaker is also absent from a joint sitting, the Deputy Chairman of Rajya Sabha presides. If he is also absent, such other person as may be determined by the members present at the joint sitting, presides over the meeting. It is clear that the Chairman of Rajya Sabha does not preside over a joint sitting as he is not a member of either House of Parliament.

The quorum to constitute a joint sitting is one-tenth of the total number of members of the two Houses. The joint sitting is governed by the Rules of Procedure of Lok Sabha and not of Rajya Sabha. If the bill in dispute is passed by a majority of the total number of members of both the Houses present and voting in the joint sitting, the bill is deemed to have been passed by both the Houses. Normally, the Lok Sabha with greater number wins the battle in a joint sitting.

The Constitution has specified that at a joint sitting, new amendments to the bill cannot be proposed except in two cases:

1. those amendments that have caused final disagreement between the Houses; and 2. those amendments that might have become necessary due to the delay in the passage of the bill.

Since 1950, the provision regarding the joint sitting of the two Houses has been invoked only thrice.

The bills that have been passed at joint sittings are:

- Dowry Prohibition Bill, 1960.20

- Banking Service Commission (Repeal) Bill, 1977.21

- Prevention of Terrorism Bill, 2002.

Budget in Parliament

The Constitution refers to the budget as the ‘annual financial statement’. In other words, the term ‘budget’ has nowhere been used in the Constitution. It is the popular name for the ‘annual financial statement’ that has been dealt with in Article 112 of the Constitution. The budget is a statement of the estimated receipts and expenditure of the Government of India in a financial year, which begins on 1 April and ends on 31 March of the following year. In addition to the estimates of receipts and expenditure, the budget contains certain other elements.

Overall, the budget contains the following: 1. Estimates of revenue and capital receipts; 2. Ways and means to raise the revenue; 3. Estimates of expenditure; 4. Details of the actual receipts and expenditure of the closing financial year and the reasons for any deficit or surplus in that year; and 5. Economic and financial policy of the coming year, that is, taxation proposals, prospects of revenue, spending programme and introduction of new schemes/projects.

The Government of India has two budgets, namely, the Railway Budget and the General Budget. While the former consists of the estimates of receipts and expenditures of only the Ministry of Railways, the latter consists of the estimates of receipts and expenditure of all the ministries of the Government of India (except the railways).

The Railway Budget was separated from the General Budget in 1921 on the recommendations of the Acworth Committee. The reasons or objectives of this separation are as follows: 1. To introduce flexibility in railway finance. 2. To facilitate a business approach to the railway policy. 3. To secure stability of the general revenues by providing an assured annual contribution from railway revenues. 4. To enable the railways to keep their profits for their own development (after paying a fixed annual contribution to the general revenues).

From 2017, there won’t be any separation between railway and general budget.

Constitutional Provisions

The Constitution of India contains the following provisions about the enactment of budget:

-

- The President shall in respect of every financial year cause to be laid before both the Houses of Parliament a statement of estimated receipts and expenditure of the Government of India for that year.

- No demand for a grant shall be made except on the recommendation of the President.

- No money shall be withdrawn from the Consolidated Fund of India except under appropriation made by law.

- No money bill imposing tax shall be introduced in the Parliament except on the recommendation of the President, and such a bill shall not be introduced in the Rajya Sabha.

- No tax shall be levied or collected except by authority of law.

- Parliament can reduce or abolish a tax but cannot increase it.

- The Constitution has also defined the relative roles or position of both the Houses of Parliament with regard to the enactment of the budget in the following way: (a) A money bill or finance bill dealing with taxation cannot be introduced in the Rajya Sabha—it must be introduced only in the Lok Sabha. (b) The Rajya Sabha has no power to vote on the demand for grants; it is the exclusive privilege of the Lok Sabha. (c) The Rajya Sabha should return the Money bill (or Finance bill) to the Lok Sabha within fourteen days. The Lok Sabha can either accept or reject the recommendations made by Rajya Sabha in this regard.

- The estimates of expenditure embodied in the budget shall show separately the expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India and the expenditure made from the Consolidated Fund of India.

- The budget shall distinguish expenditure on revenue account from other expenditure.

Expenditure and Grants

The budget consists of two types of expenditure—

- The expenditure ‘charged’ upon the Consolidated Fund of India: charged expenditure is non-votable by the Parliament (i.e. do not require approval of parliament ). It can only be discussed by the Parliament. These expenditures are sanctioned by constitution itself.

- The expenditure ‘made’ from the Consolidated Fund of India. This expenditure has to be voted by the Parliament.

The list of the charged expenditure is as follows:

- Emoluments and allowances of the President and other expenditure relating to his office.

- Salaries and allowances of the Chairman and the Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha and the Speaker and the Deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha.

- Salaries, allowances and pensions of the judges of the Supreme Court.

- Pensions of the judges of high courts.

- Salary, allowances and pension of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India.

- Salaries, allowances and pension of the chairman and members of the Union Public Service Commission.

- Administrative expenses of the Supreme Court, the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India and the Union Public Service Commission including the salaries, allowances and pensions of the persons serving in these offices.

- The debt charges for which the Government of India is liable, including interest, sinking fund charges and redemption charges and other expenditure relating to the raising of loans and the service and redemption of debt.

- Any sum required to satisfy any judgement, decree or award of any court or arbitral tribunal.

- Any other expenditure declared by the Parliament to be so charged.

Other Grants

In addition to the budget that contains the ordinary estimates of income and expenditure for one financial year, various other grants are made by the Parliament under extraordinary or special circumstances:

Supplementary Grant

It is granted when the amount authorized by the Parliament through the appropriation act for a particular service for the current financial year is found to be insufficient for that year.

Additional Grant

It is granted when a need has arisen during the current financial year for additional expenditure upon some new service not contemplated in the budget for that year.

Excess Grant

It is granted when money has been spent on any service during a financial year in excess of the amount granted for that service in the budget for that year. It is voted by the Lok Sabha after the financial year. Before the demands for excess grants are submitted to the Lok Sabha for voting, they must be approved by the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament.

Vote on account

Power of Lok Sabha (not of Rajya sabha) to authorize various ministries to incur expenditures for a part of financial year, pending the passage of appropriation bill by the parliament

Vote of Credit

It is granted for meeting an unexpected demand upon the resources of India, when on account of the magnitude or the indefinite character of the service, the demand cannot be stated with the details ordinarily given in a budget. Hence, it is like a blank cheque given to the Executive by the Lok Sabha.

Exceptional Grant

It is granted for a special purpose and forms no part of the current service of any financial year.

Token Grant

It is granted when funds to meet the proposed expenditure on a new service can be made available by reappropriation. A demand for the grant of a token sum (of Re 1) is submitted to the vote of the Lok Sabha and if assented, funds are made available. Re-appropriation involves transfer of funds from one head to another. It does not involve any additional expenditure.

Supplementary, additional, excess and exceptional grants and vote of credit are regulated by the same procedure which is applicable in the case of a regular budget.

Stages in Enactment of Budget

The budget goes through the following six stages in the Parliament:

- Presentation of budget

- presented in two parts—Railway Budget (presented first, presented by railway minister) and General Budget (presented after railway budget by finance minister).

- The Finance Minister presents the General Budget with a speech known as the ‘budget speech’. At the end of the speech in the Lok Sabha, the budget is laid before the Rajya Sabha, which can only discuss it and has no power to vote on the demands for grants.

- General discussion

- The general discussion on budget begins a few days after its presentation. It takes place in both the Houses of Parliament and lasts usually for three to four days.

- During this stage, the Lok Sabha can discuss the budget as a whole or on any question of principle involved therein but no cut motion can be moved nor can the budget be submitted to the vote of the House. The finance minister has a general right of reply at the end of the discussion.

- Scrutiny by departmental committees

- After the general discussion on the budget is over, the Houses are adjourned for about three to four weeks. During this gap period, the 24 departmental standing committees of Parliament examine and discuss in detail the demands for grants of the concerned ministers and prepare reports on them. These reports are submitted to both the Houses of Parliament for consideration.

- The standing committee system established is 1993 (and expanded in 2004) makes parliamentary financial control over ministries much more detailed, close, in-depth and comprehensive.

- Voting on demands for grants

- In the light of the reports of the departmental standing committees, the Lok Sabha takes up voting of demands for grants. The demands are presented ministry wise. A demand becomes a grant after it has been duly voted.

- the voting of demands for grants is the exclusive privilege of the Lok Sabha, that is, the Rajya Sabha has no power of voting the demands

- voting is confined to the votable part of the budget—the expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India is not submitted to the vote (it can only be discussed).

- While the General Budget has a total of 109 demands (103 for civil expenditure and 6 for defense expenditure), the Railway Budget has 32 demands. Each demand is voted separately by the Lok Sabha. During this stage, the members of Parliament can discuss the details of the budget. They can also move motions to reduce any demand for grant.

Such motions are called as ‘cut motion’, which are of three kinds:

- Policy Cut Motion It represents the disapproval of the policy underlying the demand. It states that the amount of the demand be reduced to Re 1. The members can also advocate an alternative policy.

- Economy Cut Motion It represents the economy that can be affected in the proposed expenditure. It states that the amount of the demand be reduced by a specified amount (which may be either a lumpsum reduction in the demand or omission or reduction of an item in the demand).

- Token Cut Motion It ventilates a specific grievance that is within the sphere of responsibility of the Government of India. It states that the amount of the demand be reduced by Rs 100.

A cut motion, to be admissible, must satisfy the following conditions:

- It should relate to one demand only.

- It should be clearly expressed and should not contain arguments or defamatory statements.

- It should be confined to one specific matter.

- It should not make suggestions for the amendment or repeal of existing laws.

- It should not refer to a matter that is not primarily the concern of Union government.

- It should not relate to the expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India.

- It should not relate to a matter that is under adjudication by a court.

- It should not raise a question of privilege.

- It should not revive discussion on a matter on which a decision has been taken in the same session.

- It should not relate to a trivial matter.

The significance of a cut motion lies in: (a) facilitating the initiation of concentrated discussion on a specific demand for grant; and (b) upholding the principle of responsible government by probing the activities of the government. However, the cut motion do not have much utility in practice. They are only moved and discussed in the House but not passed as the government enjoys majority support.

Their passage by the Lok Sabha amounts to the expressions of want of parliamentary confidence in the government and may lead to its resignation.

In total, 26 days are allotted for the voting of demands. On the last day the Speaker puts all the remaining demands to vote and disposes them whether they have been discussed by the members or not. This is known as ‘guillotine’.

- Passing of appropriation bill.

The Constitution states that ‘no money shall be withdrawn from the Consolidated Fund of India except under appropriation made by law’. Accordingly, an appropriation bill is introduced to provide for the appropriation, out of the Consolidated Fund of India, all money required to meet:

(a) The grants voted by the Lok Sabha.

(b) The expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India.

No such amendment can be proposed to the appropriation bill in either house of the Parliament that will have the effect of varying the amount or altering the destination of any grant voted, or of varying the amount of any expenditure charged on the Consolidated Fund of India.

The Appropriation Bill becomes the Appropriation Act after it is assented to by the President. This act authorizes (or legalizes) the payments from the Consolidated Fund of India. This means that the government cannot withdraw money from the Consolidated Fund of India till the enactment of the appropriation bill. This takes time and usually goes on till the end of April. But the government needs money to carry on its normal activities after 31 March (the end of the financial year). To overcome this functional difficulty, the Constitution has authorized the Lok Sabha to make any grant in advance in respect to the estimated expenditure for a part of the financial year, pending the completion of the voting of the demands for grants and the enactment of the appropriation bill. This provision is known as the ‘vote on account’. It is passed (or granted) after the general discussion on budget is over. It is generally granted for two months for an amount equivalent to one-sixth of the total estimation.

- Passing of finance bill

- The Finance Bill is introduced to give effect to the financial proposals of the Government of India for the following year. It is subjected to all the conditions applicable to a Money Bill.

- Unlike the Appropriation Bill, the amendments (seeking to reject or reduce a tax) can be moved in the case of finance bill.

- According to the Provisional Collection of Taxes Act of 1931, the Finance Bill must be enacted (i.e., passed by the Parliament and assented to by the president) within 75 days.

- The Finance Act legalizes the income side of the budget and completes the process of the enactment of the budget.

Funds for the Central Government

The Constitution of India provides for the following three kinds of funds for the Central government:

- Consolidated Fund of India (Article 266)

- Public Account of India (Article 266)

- Contingency Fund of India (Article 267)

Consolidated Fund of India

It is a fund to which all receipts are credited and all payments are debited. In other words, (a) all revenues received by the Government of India; (b) all loans raised by the Government by the issue of treasury bills, loans or ways and means of advances; and (c) all money received by the government in repayment of loans forms the Consolidated Fund of India. All the legally authorized payments on behalf of the Government of India are made from this fund.

- No money out of this fund can be appropriated (issued or drawn) except through grants made by parliament.

Public Account of India

- All other public money (other than those which are credited to the Consolidated Fund of India) received by or on behalf of the Government of India shall be credited to the Public Account of India.

- This includes provident fund deposits, judicial deposits, savings bank deposits, departmental deposits, remittances and so on.

- No need of Parliament’s approval